Health

Late-life depression associated with prevalent mild cognitive impairment, increased risk of dementia

Depression in a group of Medicare recipients ages 65 years and older appears to be associated with prevalent mild cognitive impairment and an increased risk of dementia, according to a report published Online First by Archives of Neurology, a JAMA Network publication.

Depressive symptoms occur in 3 percent to 63 percent of patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and some studies have shown an increased dementia risk in individuals with a history of depression.

The mechanisms behind the association between depression and cognitive decline have not been made clear and different mechanisms have been proposed, according to the study background.

Edo Richard, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues evaluated the association of late-life depression with MCI and dementia in a group of 2,160 community-dwelling Medicare recipients.

“We found that depression was related to a higher risk of prevalent MCI and dementia, incident dementia, and progression from prevalent MCI to dementia, but not to incident MCI,” the authors note.

Baseline depression was associated with prevalent MCI and dementia, while baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of incident dementia but not with incident MCI.

Patients with MCI and coexisting depression at baseline also had a higher risk of progression to dementia, especially vascular dementia, but not Alzheimer disease, according to the study results.

“Our finding that depression was associated cross sectionally with both MCI and dementia and longitudinally only with dementia suggests that depression develops with the transition from normal cognition to dementia,” the authors conclude.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

Continued high use of marijuana by the nation’s eighth, 10th and 12th graders combined with a drop in perceptions of its potential harms in this year’s Monitoring the Future survey, an annual survey of eighth, 10th, and 12th-graders conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan.

The survey was carried out in classrooms around the country earlier this year, under a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

The 2012 survey shows that 6.5 percent of high school seniors smoke marijuana daily, up from 5.1 percent five years ago. Nearly 23 percent say they smoked it in the month prior to the survey, and just over 36 percent say they smoked within the previous year.

For 10th graders, 3.5 percent said they use marijuana daily, with 17 percent reporting past month use and 28 percent reporting use in the past year. The use escalates after eighth grade, when only 1.1 percent reported daily use, and 6.5 percent reported past month use.

More than 11 percent of eighth graders said they used marijuana in the past year.

The Monitoring the Future survey also showed that teens’ perception of marijuana’s harmfulness is down, which can signal future increases in use.

Only 41.7 percent of eighth graders see occasional use of marijuana as harmful; 66.9 percent see regular use as harmful. Both rates are at the lowest since the survey began tracking risk perception for this age group in 1991.

As teens get older, their perception of risk diminishes. Only 20.6 percent of 12th graders see occasional use as harmful (the lowest since 1983), and 44.1 percent see regular use as harmful, the lowest since 1979.

A 38-year NIH-funded study, published this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that people who used cannabis heavily in their teens and continued through adulthood showed a significant drop in IQ between the ages of 13 and 38 – an average of eight points for those who met criteria for cannabis dependence.

Those who used marijuana heavily before age 18 (when the brain is still developing) showed impaired mental abilities even after they quit taking the drug. These findings are consistent with other studies showing a link between prolonged marijuana use and cognitive or neural impairment.

“We are increasingly concerned that regular or daily use of marijuana is robbing many young people of their potential to achieve and excel in school or other aspects of life,” said NIDA Director Nora D. Volkow, M.D. “THC, a key ingredient in marijuana, alters the ability of the hippocampus, a brain area related to learning and memory, to communicate effectively with other brain regions. In addition, we know from recent research that marijuana use that begins during adolescence can lower IQ and impair other measures of mental function into adulthood.”

Research clearly demonstrates that marijuana has the potential to cause problems in daily life or make a person’s existing problems worse.

In one study, heavy marijuana abusers reported that the drug impaired several important measures of well-being and life achievement, including physical and mental health, cognitive abilities, social life, and career status.

“We should also point out that marijuana use that begins in adolescence increases the risk they will become addicted to the drug,” said Volkow. “The risk of addiction goes from about 1 in 11 overall to about 1 in 6 for those who start using in their teens, and even higher among daily smokers.”

Use of other illicit drugs among teens continued a steady modest decline. For example, past year illicit drug use (excluding marijuana) was at its lowest level for all three grades at 5.5 percent for eighth graders, 10.8 percent for 10th graders, and 17 percent for 12th graders. Among the most promising trends, the past year use of Ecstasy among seniors was at 3.8 percent, down from 5.3 percent last year.

“Each new generation of young people deserves the chance to achieve its full potential, unencumbered by the obstacles placed in the way by drug use,” said Gil Kerlikowske, director of National Drug Control Policy. “These long-term declines in youth drug use in America are proof that positive social change is possible. But now more than ever we need parents and other adult influencers to step up and have direct conversations with young people about the importance of making healthy decisions. Their futures depend on it.”

The survey also looks at abuse of drugs that are easily available to teens because they are generally legal, sometimes for adults only (tobacco and alcohol), for other purposes (over-the-counter or prescribed medications; inhalants), or because they are new drugs that have not yet been banned. Most of the top drugs or drug classes abused by 12th graders are legally accessible, and therefore easily available to teens.

For the first time, the survey this year measured teen use of the much publicized emerging family of drugs known as “bath salts,” containing an amphetamine-like stimulant that is often sold in drug paraphernalia stores.

The data showed a relative low use among 12th graders at 1.3 percent. In addition, the survey measured use of the hallucinogenic herb Salvia, finding that past year use dropped among 10th and 12th graders, down to 4.4 percent for 12th graders from last year’s 5.9 percent.

Abuse of synthetic marijuana (also known as K-2 or Spice) stayed stable in 2012 at just over 11 percent for past year use among 12th graders.

While many of the ingredients in Spice have been banned by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, manufacturers attempt to evade these legal restrictions by substituting different chemicals in their mixtures.

Another drug type – inhalants – continues a downward trend. As one of the drugs most commonly used by younger students, the survey showed a past year use rate of 6.2 percent among eighth graders, a significant drop in the last five years when the 2007 survey showed a rate of 8.3 percent.

The data shows a mixed report regarding prescription drug abuse.

Twelfth graders reported non-medical use of the opioid painkiller Vicodin at a past year rate of 7.5 percent. Since the survey started measuring its use in 2002, rates hovered near 10 percent until 2010, when the survey started reporting a modest decline.

However, past year abuse of the stimulant Adderall, often prescribed to treat ADHD, has increased over the past few years to 7.6 percent among high school seniors, up from 5.4 percent in 2009.

Accompanying this increased use is a decrease in the perceived harm associated with using the drug, which dropped nearly 6 percent in the past year—only 35 percent of 12th graders believe that using Adderall occasionally is risky. The survey continues to show that most teens who abused prescription medications were getting them from family members and friends.

The survey also measured abuse of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines containing dextromethorphan-5.6 percent of high school seniors abused them in the past year, a rate that has held relatively steady over the past five years.

The 2012 results also showed a continued steady decline in alcohol use, with reported use at its lowest since the survey began measuring rates.

More than 29 percent of eighth graders said they have used alcohol in their lifetime, down from 33.1 percent last year, and significantly lower that peak rate of 55.8 percent in 1994.

For 10th graders, 54 percent of teens reported lifetime use of alcohol, down from its peak of 72 percent in 1997.

Binge drinking rates (five or more drinks in a row in the previous two weeks) have been slowly declining for eighth graders, at 5.1 percent, down from 6.4 percent in 2011, and 13.3 percent at their peak in 1996.

Cigarette smoking continues at its lowest levels among eighth, 10th and 12th graders, with dramatic long-term improvement.

Significant declines were seen in lifetime use among eighth graders, down to 15.5 percent from last year’s 18.4 percent, compared to nearly 50 percent at its peak in 1996. Significant declines were also seen in 10th grade lifetime use of cigarettes, down to 27.7 percent from 30.4 percent in 2011. Peak rates for 10th graders were seen in 1996 at 61.2 percent.

For some indicators, including past month use in all three grades, cigarette smoking remains lower than marijuana use, a phenomenon that began a few years ago.

The survey also measures several other kinds of tobacco delivery products. For example, past year use of small cigars was reported at nearly 20 percent for 12th graders, with an 18.3 percent rate for hookah water pipes.

“We are very encouraged by the marked declines in tobacco use among youth. However, the documented use of non-cigarette tobacco products continues to be a concern,” said Howard K. Koh, M.D., M.P.H., assistant secretary for health for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “Preventing addiction includes helping kids be tobacco free so they can enjoy a fighting chance for health.”

Overall, 45,449 students from 395 public and private schools participated in this year’s Monitoring the Future survey.

Since 1975, the survey has measured drug, alcohol, and cigarette use and related attitudes in 12th-graders nationwide. Eighth and 10th graders were added to the survey in 1991.

Survey participants generally report their drug use behaviors across three time periods: lifetime, past year, and past month. Questions are also asked about daily cigarette and marijuana use. NIDA has provided funding for the survey since its inception by a team of investigators at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, led by Dr. Lloyd Johnston.

Additional information on the MTF Survey, as well as comments from Dr. Volkow, can be found at www.drugabuse.gov/drugpages/MTF.html .

- Details

- Written by: Editor

People who study or treat Alzheimer’s disease and its earliest clinical stage, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), have focused attention on the obvious short-term memory problems.

But a new study suggests that people on the road to Alzheimer’s may actually have problems early on in processing semantic or knowledge-based information, which could have much broader implications for how patients function in their lives.

Terry Goldberg, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at the Hofstra North Shore-LIJ School of Medicine and director of neurocognition at the Litwin Zucker Center for Research in Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders at The Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, NY, said that clinicians have observed other types of cognitive problems in MCI patients but no one had ever studied it in a systematic way.

Many experts had noted individuals who seemed perplexed by even the simplest task. In this latest study, published in this month’s issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry, investigators used a clever series of tests to measure a person’s ability to process semantic information.

Do people with MCI have trouble accessing different types of knowledge? Are there obvious semantic impairments that have not been picked up before? The answer was “yes.”

In setting out to test the semantic processing system, Dr. Goldberg and his colleagues needed a task that did not involve a verbal response. That would only confuse things and make it harder to interpret the results.

They decided to use size to test a person’s ability to use semantic information to make judgments between two competing sets of facts.

“If you ask someone what is bigger, a key or an ant, they would be slower in their response than if you asked them what is bigger, a key or a house,” explained Dr. Goldberg.

The greater the difference in size between two objects, the faster a person – normal or otherwise – can recognize the difference and react to the question.

Investigators brought in 25 patients with MCI, 27 patients with Alzheimer’s and 70 cognitively fit people for testing. They found large differences between the healthy controls and the MCI and Alzheimer’s patients.

“This finding suggested that semantic processing was corrupted,” said Dr. Goldberg. “MCI and AD (Alzheimer’s disease) patients are really affected when they are asked to respond to a task with small size differences.”

They then tweaked the task by showing pictures of a small ant and a big house or a big ant and a small house.

This time, the MCI and AD patients did not have a problem with the first part of the test – they were able to choose the house over the ant when asked what was bigger.

But if the images were incongruent – the big ant seemed just as big as the small house – they were confused, they answered incorrectly or took longer to arrive at a response.

Patients with MCI were functioning somewhere between the healthy people and those with AD. “When the decision was harder, their reaction time was slower,” he said.

Would this damaged semantic system have an effect on everyday functions? To answer this question, investigators turned to the UCSD Skills Performance Assessment scale, a tool that they have been using in MCI and AD patients that is generally used to identify functional deficits in patients with schizophrenia. The test taps a person’s ability to write a complex check or organize a trip to the zoo on a cold day.

This is actually a good test to figure out whether someone has problems with semantic knowledge. Semantic processing has its seat in the left temporal lobe.

“The semantic system is organized in networks that reflect different types of relatedness or association,” the investigators wrote in their study. “Semantic items and knowledge have been acquired remotely, often over many repetitions, and do not reflect recent learning.”

Dr. Goldberg said the finding is critically important because it may be possible to strengthen these semantic processing connections through training.

“It tells us that something is slowing down the patient and it is not episodic memory but semantic memory,” he said.

They will continue to study these patients over time to see if these semantic problems get worse as the disease advances.

In an accompanying editorial, David P. Salmon, PhD, of the Department of Neurosciences at the University of California in San Diego, said that the “semantic memory deficit demonstrated by this study adds confidence to the growing perception that subtle decline in this cognitive domain occurs in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

Because the task places minimal demands on the effortful retrieval process, overt word retrieval, or language production, it also suggests that this deficit reflects an early and gradual loss of integrity of semantic knowledge.”

He added that a “second important aspect of this study is the demonstration that semantic memory decrements in patients with mild cognitive impairment may contribute to a decline in the ability to perform usual activities of daily living.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor

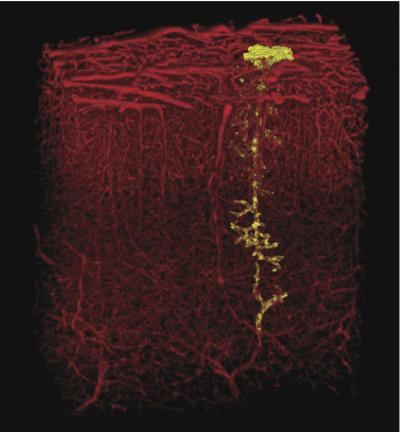

Blocking a single tiny blood vessel in the brain can harm neural tissue and even alter behavior, a new study from the University of California, San Diego has shown.

But these consequences can be mitigated by a drug already in use, suggesting treatment that could slow the progress of dementia associated with cumulative damage to miniscule blood vessels that feed brain cells.

The team reported its results in the Dec. 16 advance online edition of Nature Neuroscience.

“The brain is incredibly dense with vasculature. It was surprising that blocking one small vessel could have a discernable impact on the behavior of a rat,” said Andy Y. Shih, lead author of the paper who completed this work as a postdoctoral fellow in physics at UC San Diego. Shih is now an assistant professor at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Working with rats, Shih and colleagues used laser light to clot blood at precise points within small blood vessels that dive from the surface of the brain to penetrate neural tissue. When they looked at the brains up to a week later, they saw tiny holes reminiscent of the widespread damage often seen when the brains of patients with dementia are examined as a part of an autopsy.

These micro-lesions are too small to be detected with conventional MRI scans, which have a resolution of about a millimeter. Nearly two dozen of these small vessels enter the brain from a square millimeter area of the surface of the brain.

“It’s controversial whether that sort of damage has consequences, although the tide of evidence has been growing as human diagnostics improve,” said David Kleinfeld, professor of physics and neurobiology, who leads the research group.

To see whether such minute damage could change behavior, the scientists trained thirsty rats to leap from one platform to another in the dark to get water.

The rats readily jump if they can reach the second platform with a paw or their snout, or stretch farther to touch it with their whiskers. Many rats can be trained to rely on a single whisker if the others are clipped, but if they can’t feel the far platform, they won’t budge.

“The whiskers line up in rows and each one is linked to a specific spot in the brain,” Shih said. “By training them to use just one whisker, we were able to distill a behavior down to a very small part of the brain.”

When Shih blocked single microvessels feeding a column of brain cells that respond to signals from the remaining whisker, the rats still crossed to the far platform when the gap was small. But when it widened beyond the reach of their snouts, they quit.

The FDA-approved drug memantine, prescribed to slow one aspect of memory decline associated with Alzheimer’s disease, ameliorated these effects. Rats that received the drug jumped whisker-wide gaps, and their brains showed fewer signs of damage.

“This data shows us, for the first time, that even a tiny stroke can lead to disability,” said Patrick D. Lyden, a co-author of the study and chair of the department of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “I am afraid that tiny strokes in our patients contribute—over the long term—to illness such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease,” he said, adding that “better tools will be required to tell whether human patients suffer memory effects from the smallest strokes.”

“We used powerful tools from biological physics, many developed in Kleinfeld’s laboratory at UC San Diego, to link stroke to dementia on the unprecedented small scale of single vessels and cells,” Shih said. “At my new position at MUSC, I plan to work on ways to improve the detection of micro-lesions in human patients with MRI. This way clinicians may be able to diagnose and treat dementia earlier.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor