Health

BERKELEY, Calif. – Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have put the squeeze – literally – on malignant mammary cells to guide them back into a normal growth pattern.

The findings, presented Monday at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in San Francisco, show for the first time that mechanical forces alone can revert and stop the out-of-control growth of cancer cells.

This change happens even though the genetic mutations responsible for malignancy remain, setting up a nature-versus-nurture battle in determining a cell’s fate.

“We are showing that tissue organization is sensitive to mechanical inputs from the environment at the beginning stages of growth and development,” said principal investigator Daniel Fletcher, professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley and faculty scientist at the Berkeley Lab. “An early signal, in the form of compression, appears to get these malignant cells back on the right track.”

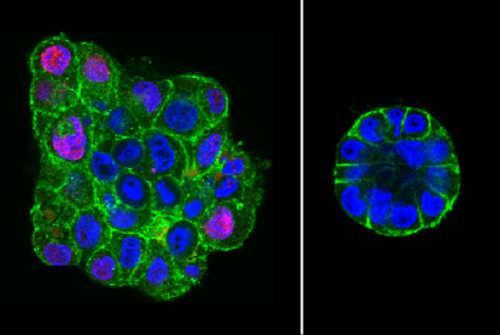

Throughout a woman’s life, breast tissue grows, shrinks and shifts in a highly organized way in response to changes in her reproductive cycle. For instance, when forming acini, the berry-shaped structures that secrete milk during lactation, healthy breast cells will rotate as they form an organized structure. And, importantly, the cells stop growing when they are supposed to.

One of the early hallmarks of breast cancer is the breakdown of this normal growth pattern. Not only do cancer cells continue to grow irregularly when they shouldn’t, recent studies have shown that they do not rotate coherently when forming acini.

While the traditional view of cancer development focuses on the genetic mutations within the cell, Mina Bissell, Distinguished Scientist at the Berkeley Lab, conducted pioneering experiments that showed that a malignant cell is not doomed to become a tumor, but that its fate is dependent on its interaction with the surrounding microenvironment.

Her experiments showed that manipulation of this environment, through the introduction of biochemical inhibitors, could tame mutated mammary cells into behaving normally.

The latest work from Fletcher’s lab, in collaboration with Bissell’s lab, takes a major step forward by introducing the concept of mechanical rather than chemical influences on cancer cell growth. Gautham Venugopalan, a member of Fletcher’s lab, conducted the new experiments as part of his recently completed Ph.D. Dissertation at UC Berkeley.

“People have known for centuries that physical force can influence our bodies,” said Venugopalan. “When we lift weights, our muscles get bigger. The force of gravity is essential to keeping our bones strong. Here we show that physical force can play a role in the growth – and reversion – of cancer cells.”

Venugopalan and collaborators grew malignant breast epithelial cells in a gelatin-like substance that had been injected into flexible silicone chambers. The flexible chambers allowed the researchers to apply a compressive force in the first stages of cell development.

Over time, the compressed malignant cells grew into more organized, healthy-looking acini that resembled normal structures, compared with malignant cells that were not compressed. The researchers used time-lapse microscopy over several days to show that early compression also induced coherent rotation in the malignant cells, a characteristic feature of normal development.

Notably, those cells stopped growing once the breast tissue structure was formed, even though the compressive force had been removed.

“Malignant cells have not completely forgotten how to be healthy; they just need the right cues to guide them back into a healthy growth pattern,” said Venugopalan.

Researchers further added a drug that blocked E-cadherin, a protein that helps cells adhere to their neighbors. When they did this, the malignant cells returned to their disorganized, cancerous appearance, negating the effects of compression and demonstrating the importance of cell-to-cell communication in organized structure formation.

It should be noted that the researchers are not proposing the development of compression bras as a treatment for breast cancer. “Compression, in and of itself, is not likely to be a therapy,” said Fletcher. “But this does give us new clues to track down the molecules and structures that could eventually be targeted for therapies.”

The National Institutes of Health helped fund this research through its Physical Science-Oncology program.

Sarah Yang writes for the UC Berkeley News Center.

- Details

- Written by: Sarah Yang

LAKEPORT, Calif. – A stroke support group will meet on Wednesday, Dec. 19.

The group will meet from 1 p.m. to 2 p.m. at the Sutter Lakeside Hospital conference room, 5176 Hill Road East, Lakeport.

Strokes can happen to anyone, regardless of age.

If you or a loved one has experienced a stroke and you need access to specific services, as well as a community who understands, join the group to provide input about ways they can meet your needs.

For more information, call Ruth Lincoln, clinical nurse and staff educator, at 707-262-5032.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

LAKEPORT, Calif. – Beginning Thursday, Jan. 24, Sutter Pacific Medical Foundation will offer the fourth session of Weigh to Go Challenge at Lakeside Wellness Center.

The Weigh to Go Challenge is a 16-week program that includes many support modalities to assist with positive lifestyle changes on the road to better health and weight management.

This challenge is open to the public includes gym membership, nutritional consultation, fitness room orientation and guidance, wellness coaching, monthly education classes and weekly weigh-ins.

Also offered are exclusive fitness classes for class participants only and personal one-on-one trainings.

The cost of this program is $100 for the program and is limited to the first 20 participants.

Please call today to reserve your space. Sign-ups are happening now until Jan. 16.

Call the Wellness Center office for more details at 707-262-5171 or find them on Facebook at Sutter Lakeside Wellness Center.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

Three University of Kentucky (UK) sociologists have co-authored a study that helps to fill a gap in our understanding of suicide risk among African-American women.

Appearing in the December issue of Social Psychology Quarterly (SPQ), the study, “Too Much of a Good Thing? Psychosocial Resources, Gendered Racism, and Suicidal Ideation among Low Socioeconomic Status African American Women,” examines the relationship between racial and gender discrimination and suicidal ideation, or thinking about and desiring to commit suicide.

The co-authors of the study include assistant professor Brea L. Perry, associate professor Carrie B. Oser, and Ph.D. Candidate Erin L. Pullen, all from the UK Department of Sociology.

In basic terms, the study investigates risk and protective factors for mental health among African-American women with low socioeconomic status.

The researchers found that women who have experienced more race and gender-based discrimination have a higher risk of suicidal ideation than women who have experienced less discrimination, which reinforces previous research on the positive correlation between discrimination and poor mental health.

However, the study goes even further to examine whether different psychosocial resources such as eudemonic well-being (sense of purpose in life), self-esteem, and active coping – that have traditionally been found to be protective of mental health among white Americans – can buffer the effects of racial and gender discrimination on suicidal ideation among low socioeconomic status African-American women.

Perry said that some of the findings were unexpected.

“We were somewhat surprised to find that moderate levels of eudemonic well-being, self-esteem, and active coping are protective, while very high and low levels are not,” Perry said.

The SPQ study used data from 204 predominantly low-income African-American women, collected as part of the Black Women in the Study of Epidemics (B-WISE) project.

The SPQ study has helped to fill a gap in knowledge about suicide risk among African-American women, which is important because recent research suggests that rates of suicide attempt are high in this group.

The UK researchers said they hope the SPQ study positively impacts students.

“I hope that this study can inform identification of African-American students who are at risk for suicidal ideation and point to some potential interventions for coping with discrimination,” Perry said.

Perry believes the most important lesson learned from this study is that it is critical to examine culturally specific risks and protective processes in mental health.

“These findings demonstrate that it is not sufficient to simply study African-American women as one small part of an aggregated sample composed largely of whites,” Perry said. “When we take that approach, we completely miss what is going on in smaller, underrepresented groups. We cannot assume that what is protective for white men, for example, is also protective for African-American women. There are specific historical and cultural circumstances and lived experiences that are unique to each racial and gender group, and these differentially shape factors that increase or decrease vulnerability and resilience.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor