- Elizabeth Larson

Judge dismisses pot case due to sheriff violating defendant's Miranda rights; sheriff blames prosecutors

LAKEPORT, Calif. – This week a judge dismissed a marijuana cultivation and sales case after finding that the county's sheriff violated the defendant's Miranda rights.

In the interest of justice, Judge Andrew Blum dismissed the case against Frank Phillip Frazza, 24, of Kelseyville during a Wednesday morning preliminary hearing after determining Sheriff Frank Rivero violated Frazza's Fifth Amendment right to counsel.

Senior Deputy District Attorney Art Grothe, who handled the prosecution, said the case can't be refiled. “It's gone,” he said.

In Grothe's 24 years as a prosecutor, he said he's never seen so significant of a case thrown out due to this type of Miranda violation.

Frazza's defense attorney Mike Wise said he also hasn't seen anything like the particular Miranda violation in his decades of practice.

District Attorney Don Anderson said the Miranda violation “really gutted the case so we had very little evidence left.”

Anderson said Rivero's refusal to provide additional information to the District Attorney's Office about his actions in the case also harmed the prosecution.

But in a Friday statement, Rivero blamed the situation on the District Attorney's Office.

“I believe Frazza should have been held to stand trial during his preliminary hearing, but the absence of rigorous prosecution resulted in the dismissal of a good case,” Rivero said in a written statement.

Frazza, who local court records show has no other criminal cases on his record, was charged with marijuana cultivation and possession of marijuana for sale in the case.

On Aug. 2, 2012, Rivero and other sheriff's personnel, along with code enforcement and state fish and game officials, arrived at his grow site on Cantwell Ranch Road near Lower Lake.

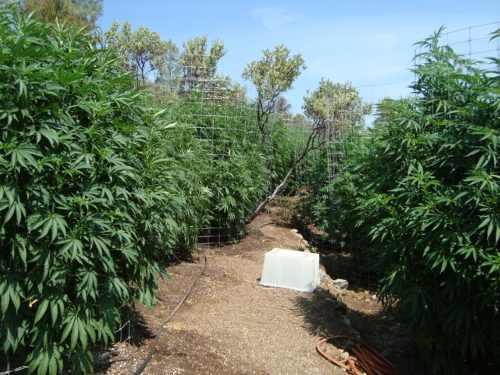

There, they eradicated 73 large plants – each about 7 feet tall. Grothe said sheriff's officials estimated the crop would have been worth about $600,000.

When Rivero arrived, Frazza was on the phone with a female attorney. According to Frazza's sworn statement included in court documents, Rivero told him to get off the phone, saying, “You don’t need to be talking to him, you need to be taking to me.”

“You can't do that,”Anderson said of the actions Rivero took in interfering with Frazza's discussion with his attorney. “That is such a clear violation of Miranda. Anybody in the academy would know that.”

Wise said the real Miranda issue – which guarantees the right to remain silent – was when Rivero directed Frazza to talk to law enforcement when he wasn't required to do so.

“You're telling someone that's in a custodial situation, 'You’re obligated to talk to law enforcement,' without first giving them their Miranda rights; that's a violation of the Constitution,” Wise said.

At the scene, Rivero wouldn't speak to Frazza's attorney on the phone. On the attorney's advice Frazza cooperated with Rivero's demands and unlocked the gate to allow entry to the property.

Wise said Frazza called his attorney because he was making his “very best efforts” to follow the law. The other attorney had given Frazza a large packet of information on state marijuana law to help him follow the rules.

“In his mind he was complying with the law,” said Wise, and when Frazza saw authorities arriving at the property, he called the attorney to ask what he should do next and was interrupted in the process.

According to court records, Frazza presented deputies with an envelope filled with medical recommendations which he said they refused to look at.

A sheriff's report on Frazza's arrest said he claimed to be growing for a Los Angeles collective and did not know any of the subjects listed on the recommendations. His grow was determined to be in violation of Lake County's marijuana cultivation ordinance, which had been approved the previous month.

Sheriff takes the stand

During Wednesday's hearing, Rivero made an appearance in court, taking the stand and answering questions about his role in the case.

Rivero claimed he didn’t remember a number of aspects of the case, including making the statement to Frazza to get off the phone.

Rivero had repeated that statement in a meeting of county officials last year, according to Grothe and Anderson, who were present. The meeting, they said, was to discuss how to enforce the county's marijuana cultivation ordinance.

On the stand Wednesday Rivero said he didn't recall that meeting, nor did he remember seeing email requests last year from Grothe, who was seeking a supplemental report on the Frazza case.

While Rivero said he didn't remember seeing or reviewing those emails, an email exchange between the sheriff and Grothe was submitted into the court record. It showed that Rivero had not only reviewed Grothe's request but refused to fulfill it.

After an initial request went unanswered in August 2012, on Sept. 10, 2012, Grothe sent Rivero a second formal request for a supplemental report “detailing timing, circumstances, and content of any communications between himself and defendant, specifically including statements concerning defendant's attempt to, or concerns about, telephoning his attorney.”

On Sept. 13, 2012, Rivero asked Capt. Chris Macedo to ask what other information Grothe wanted. “I only transported the suspects,” Rivero wrote.

After Grothe repeated his request in writing, Macedo forwarded him a Sept. 20 email in which Rivero said Frazza “got on the phone to his attorney and told us that she (the attorney) wanted to talk to us. I said that we would not talk to her.”

He said he transported the suspects and did a recording of their statements, with the recording provided. “This does not merit a supplemental,” Rivero wrote.

Regarding Rivero's statements that he couldn't recall those key details, Wise said, “The sheriff's demeanor in this particular case, where he testified, in my personal opinion was not consistent with it being a legitimate failure to recall details.”

Rivero's credibility on and off the stand has been an ongoing issue after Anderson determined earlier this year that Rivero had lied about his role in a nonfatal 2008 shooting.

Anderson's office is required to disclose to criminal defendants in any case in which Rivero is a material witness that he is a “Brady” officer.

“Brady” comes from the US Supreme Court case requiring the government to disclose to criminal defendants any information that could clear them, including information related to the credibility of officers involved in their cases.

Wise moved to have a significant amount of the evidence suppressed – including marijuana samples, marijuana recommendations, the binder of law documents prepared by Frazza's other attorney, and statements by Rivero, and deputies Lucas Bingham and Dennis Keithly – alleging they were taken during illegal search and seizure.

Rivero and Macedo also were ordered to turn over all correspondence with the District Attorney's Office on the case.

Wise credited Grothe with being an “honest, straight shooter” who had made multiple attempts to get the sheriff to clarify, in writing, the actions he took at Frazza's property. “But, unfortunately, he wouldn't,” Wise said of Rivero.

After considering the evidence, Blum dismissed the case.

As for whether Frazza might sue over the eradicated marijuana, Wise said he doesn't know. “That's the second half of the conversation that we haven't finished yet.”

Email Elizabeth Larson at

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?