This week in history features an executive order with a lasting impact.

Feb. 19, 1942

On this day in history, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

It was just months following the Japanese attack on the naval port at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and Americans were justifiably anxious about foreign invasion. After all, the long coast stretching from San Diego in the south to the Aleutian Islands in the north gave the Japanese plenty of options for amphibious assault and practically unfettered access to American airspace.

To be sure, the military had long since identified this coast as the soft underbelly of the nation and had taken steps to gird it in concrete artillery bunkers, in sunken anti-aircraft posts and in hilltop observation stations.

Our very own Lake County featured several such observation stations, which were manned by watchful citizens around the clock.

Locals from the Cobb area still remember the observation post that was stationed on Seigler Mountain, and some even remember taking their turns inside the wooden shed watching the passing clouds for signs of Japanese bombers.

As thorough as these precautions seemed, they were deemed insufficient to actually prevent major invasions.

Sure, a well-stocked artillery could help defend against a frontal assault and the observation posts could notify the nearest air force base of the need to scramble the fighters in defense, but none of these actually prevented a thing. Moreover, none of these precautions were effective against the single most feared enemy action: sabotage.

No matter how thick the concrete bunker, how far-ranged the artillery, or how keen the eye of the observer, a single subvert action on the part of a Japanese spy could undo all this work.

A single saboteur could guide the incoming thrust of the enemy blade past these precautions and deep into the belly of the nation.

Our nation’s security was at stake; the lives of our women and children were at stake. Something had to be done. Steps had to be taken to effectively counter the use of Japanese spies along the coast. The only sure-fire way to defend our nation under these circumstances was to contain those among us with ties to the Empire of Japan, those who posed a threat to our national security: the Japanese immigrants.

Of course, steps also had to be taken to actually protect these same immigrants. After all, by 1942 the Pacific coast states had already had a century-long history of vigilante violence against people of Asian descent.

The prejudice against Chinese immigrants working in local mines in Lake County is a well-established fact. So, too, is the fact that this prejudice occasionally translated into acts of violence, like that one time a small riot in Lakeport resulted in the broken windows and scarred door of a Chinese laundromat.

However, this prejudice was not just saved for the Chinese. In a 1913 advertisement that ran in newspapers in Sacramento, Lake County boosters tried to convince people of the benefits of buying land around Clear Lake. One of their selling points was that not a single Japanese person owned land within the boundary of Lake County.

To make matters worse, the bodies of those killed during the attack on Pearl Harbor were still making their way back to their families and ultimate burial. Passions were high against Japanese-Americans. It would be best for all parties involved to separate those of Japanese descent from the rest of the population.

These, at least, were the arguments used to justify Executive Order 9066.

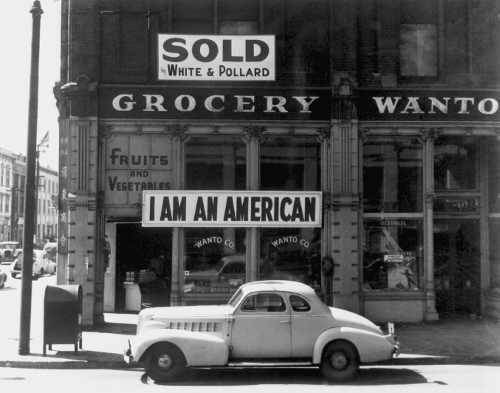

In what later went down in infamy as one of the greatest injustices perpetrated against American citizens by the American government, Executive Order 9066 legalized the detention of all Japanese-Americans who lived within the Pacific military zone, a somewhat arbitrary line that stretched from the rim of the Cascade Mountains in Washington and Oregon directly south through California.

Americans with Japanese heritage and Japanese aliens living within the military zone were forcibly removed from their homes and gathered within the walls of detention facilities.

Within a month, 110,000 people in California, Oregon and Washington had been moved to internment camps. They remained there until Dec. 17, 1944.

Later, when told that he had been interned for his own safety, one internee famously retorted, “If we were put there for our own protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

It would take decades before the American government acknowledged the immorality of Executive Order 9066.

Certainly, there did exist a viable threat from Japanese spies and anger over the attack on Pearl Harbor resulted in vigilante assaults on people of Japanese descent.

Nevertheless, the basic tenets of American freedom were violated that February day in 1942 – a fact that President Ronald Reagan acknowledged when he signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. In this show of regret and sincere apology, the American government granted reparations to the families who lost so much during their internment.

For many it was too little, too late.

Some of the detention facilities remain to this day, haunting ghost towns of an embarrassing chapter in our history.

If you are curious, and the mood ever strikes you, go visit Manzanar Relocation Center due east of Visalia. As a national historic site, it preserves the stories of those internees who lived two years in the detention facility.

A museum onsite chronicles the daily lives and struggles they experienced and a guided tour with a ranger will bring to life the now ruined barracks where internees once slept.

Our history is full of the beautiful, the heroic and the patriotic. But hidden in the dark corners of American history books can be found accounts like Executive Order 9066.

The full scope of our collective past – warts and all – have made this country what it is today. So if you hope to visit the memorial site of Pearl Harbor someday, consider also planning a trip down south to a memorial far less gratifying, but no less important.

For details about Manzanar National Historic Site, visit https://www.nps.gov/manz/index.htm .

Antone Pierucci is the former curator of the Lake County Museums in Lake County, Calif.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?