This week’s historical highlight marks the first step in setting rules for immigration to the United States of America.

March 26, 1790

For better or worse, the history of laws concerning immigration and citizenship in the United States is one of exclusion.

That America has become a melting pot of different cultures and races is, in many ways, despite these laws, rather than because of them. On the books, we’ve done our best to be monocultural, but humans are often less manageable in reality than they are on paper.

In the 21st century, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services control both immigration and the process of becoming a citizen.

Today, someone can become an American citizen either at birth (by being born in the country or certain territories) or after birth (primarily through naturalization). In both cases, the requirements for immigration and citizenship have developed over the course of decades and represent the culmination of a contentious history.

Immigration and citizenship have always been wrapped up in our national identity, as we as a people grapple with the question of what it means to be an American and the types of people who fit that archetype. At the heart of laws governing citizenship in any country is the unspoken understanding that some people aren’t fit to become one. There is a filtering process.

On this day in 1790, the United States government took the first step towards defining the parameters of our own filter.

The Naturalization Act of 1790 established the first criteria for the process of becoming a naturalized American citizen.

The law itself required an immigrant to have lived within the United States for at least two years and to be a free, white person of good standing. The individual’s citizenship was extended to any children under the age of 21, regardless of their birthplace.

By the wording of this law, the very first of its kind in America, a large swathe of the world was excluded from the possibility of gaining citizenship (Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, African etc.).

Five years later, the 1790 law was replaced with a new one, which put even stricter constraints on naturalization by extending the minimum number of years in residence from two to five. A few years later, that was extended to 14, only to be reduced once more to five in 1802.

It would only be grudgingly that America expanded the circle of acceptable, potential citizens. The Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 granted citizenship to people born within the United States and subject to its jurisdiction (including former slaves).

The Naturalization Act of 1870, five years following the end of the Civil War, even extended the naturalization laws to “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.”

However, as if to backtrack from the slight expansion created in the 1860s, the next several decades were spent excluding people of Asian descent, with the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

This act itself was the culmination of a decades-long battle over the issue of Chinese immigration and labor in the western United States, a history that played out in bloody riots across the region (hyperlink to former article on Chinese riots).

Even the children of these Chinese aliens were unable to claim American citizenship, until the ruling of a court in the 1890s changed that restriction. The final restrictions on people of Asian descent becoming citizens were finally lifted following the Second World War.

If Africans and Asian immigrants had trouble becoming American citizens, it was downright impossible for Native Americans.

It is somewhat ironic that the one group of people who faced the fiercest battle for citizenship were those whose ancestors have called this land home for millennia – but history is full of such sad ironies.

Throughout most of the 19th century, American Indians were forbidden citizenship, a status that gradually began to break down as the 20th century dawned.

In California, most American Indians were granted citizenship following the 1916 state Supreme Court case involving a Lake County Pomo, Ethan Anderson, and the county recorder, Shaffer Matthews. All American Indians were finally granted full citizenship in 1924.

After hard-won victories, different races were eventually able to carve out their place at the American table, but only after decades of prejudice and countless court cases.

In one form or another, the laws governing the granting of citizenship to immigrants remained prejudicial until the middle of the 20th century.

Finally, in 1952 Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act, which forbade discrimination during the citizenship process based on race and gender.

As you can see from this litany of laws, acts and amendments, America has always been rather specific in the types of people it has wanted as citizens.

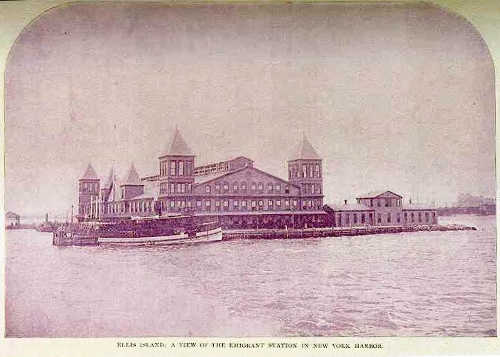

Historically, Lady Liberty’s illuminating lamp was more often used to get a closer look at those huddled masses than as a beacon of welcome to all.

The laws that are created in the coming years will determine if we can break from our history or are irrevocably chained to it.

Antone Pierucci is the former curator of the Lake County Museum and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?