It didn’t take long for Theodore Judah’s dream to suffocate under the greed of his colleagues.

In their defense, they never gave Judah the impression that they were anything but what they were: capitalists. Money, and the making of it, was their one and only goal. How else do you get three merchants and a grocer to risk their fortunes on such a crazy scheme as building a railroad across the country?

Of course, that’s not to say it was a sure thing. In fact, it was completely bonkers. None of them had the faintest idea of how to build a railroad. All they had ever built themselves were shops in Sacramento and their own prestige.

But, that’s where Theodore Judah, the engineer, was to play his part.

Judah had long dreamt of a railroad that would connect California with the rest of America; one that would span from sea to sea. Sure, people scoffed and laughed at “Crazy Judah” but he didn’t mind. He had a dream and soon, he had proof of his serious intentions to follow up on that dream.

In 1856, after much planning, Judah and a group of investors finished work on the Sacramento Valley Line – the first railroad west of the Missouri River. In 1859 he was nominated by the California Pacific Railroad Convention to take his plans of a transcontinental railroad to Washington D.C.

He took his dream with him, eager to share the brilliance of it with those who had the ability to make it happen. Even back then, D.C. had a reputation for devouring the innocent, and within no time, Judah realized he was in over his head.

To be fair, his timing was off.

The Civil War loomed over the horizon and sectionalism paralyzed Congress. The plans he proposed to the politicians fell atop a heap of other equally ambitious projects that were looking for federal funding. It was a large heap.

You see, already the federal government was proving itself a lucrative source of money for businessmen. All a budding entrepreneur had to do was figure out a way of dovetailing his own personal interests with something the government wanted.

Heck, some even didn’t even try to mask what they were doing – they didn’t need to. After all, this was the time of the ambitious and completely daft plan to outfit American cavalrymen in the arid southwest with camels instead of horses (a project pushed for by soon-to-be Confederate President Jefferson Davis in 1858). If Uncle Sam paid for imported camels, he clearly didn’t scrutinize the federal funding package very closely.

Even still, it looked as if Judah’s plans had fallen on deaf ears. He returned to California with another plan in mind. He needed private investors to put money into the project first. That would convince the politicians back east of the feasibility of his plan. Because no one in 1860s America would put good money on a bad project, right?

All Judah had to do was pop his head outside the window in his office in Sacramento to find four likely investors. By now, their names are well known. The Big Four they would be called: Huntington, Crocker, Stanford, Hopkins. They would grow to become giants of American capitalism, but when Judah first approached them in the early 1860s, they were nothing but four well-to-do local businessmen. But they were businessmen willing to take a risk on a crazy plan.

With a new set of investors in hand, Judah made the long journey back to Washington D.C.– a journey by boat to the isthmus of Central America, then by riverboat down the snaking rapids until reaching the far coast and boarding yet another boat, this one bound for the east coast.

By the time he returned to D.C., the war had finally broken loose and Congress – which had suffered from entrenched gridlock between Republicans and Democrats before – now found itself ruled by a single party. And that party liked the idea of consolidating its far-off states by connecting them with a railroad. And so the Pacific Railroad Act passed through the halls of power in 1862. Theodore Judah was about to realize his dream.

But this isn’t a fairytale and life is tough. It certainly was for Theodore Judah.

After returning to California with the good news, he had a falling out with his business partners. The Big Four had plans of their own, plans to squeeze this federal deal for all the money it was worth. The efficiency and quality of the resulting railroad didn’t matter to them at the time. Their vision for the company diverged greatly from that of Theodore Judah.

Disenchanted, Judah boarded a ship once more, this time for New York, where he hoped to find better partners. Unfortunately, his luck failed him and he contracted yellow fever from an infected mosquito during his journey across Central America. He died soon after.

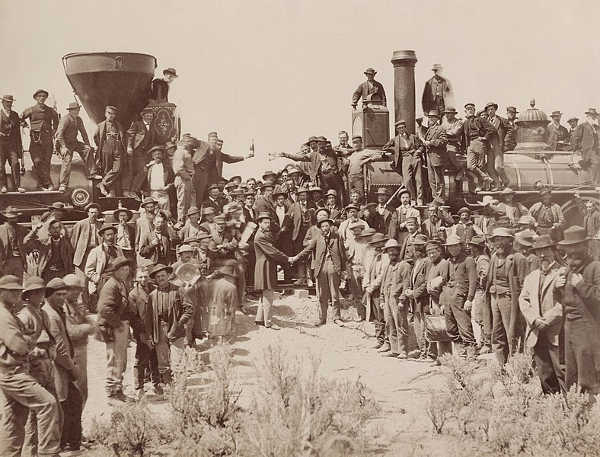

Six years later, on May 10, 1869, the final spike for the new transcontinental railroad was driven home, the memory of the man who first envisioned it far from everyone’s mind.

Antone Pierucci is curator of history at the Riverside County Park and Open Space District and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?