America has certainly seen its fair share of noteworthy political speeches.

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and George Washington’s Farewell Speech number somewhere among the top.

We’ve also seen some stinkers, from William Henry Harrison’s presidential inauguration speech that lasted hours and went nowhere but to his early demise from when he contracted pneumonia to any one of Jimmy Carter or George W. Bush’s speeches where they mispronounced “nuclear.”

But possibly the most tone-deaf speech of them all came from one of America’s greatest political thinkers: Alexander Hamilton.

Hamilton was born and raised in the East Indies – the Caribbean – until he travelled to British Colonial America to attend college.

While attending Kings College (later Columbia University) in New York City, young Hamilton made a name for himself as an adroit orator and cutting political essayist. Hamilton’s politics would always tend towards the elitist, believing that the best government was the one with the most mechanisms in place to limit direct democracy. His was a government of a strong central authority, a government many suspected closely resembled England’s monarchy.

After the war, as the new nation struggled to survive a deep economic recession, the leading politicians gathered in Philadelphia to rethink how they operated their government.

Back in 1775-76, the Continental Congress first wrote the Articles of Confederation. At the time, winning the war against England looked like a longshot.

When the separate colonies came together to oppose English aggression, they needed a document that laid out the powers of each colony and how they were supposed to cooperate to win the war.

The result of these deliberations: the Articles of Confederation. The fundamental flaw, as far as men like Alexander Hamilton and George Washington were concerned, was that under the Articles, each colony (soon-to-be state) was a sovereign country.

As independent entities, they agreed to join in confederation. Each colony, through its delegates elected to Congress, had equal say on matters relating to the confederacy. Every piece of legislation had to be unanimously agreed to – meaning just a single colony could hold up Congress indefinitely.

This had been the primary culprit for the chronic lack of supplies that time and again nearly starved Washington’s army during the war. After a decade being the law of the land, the Articles of Confederation had reached their end.

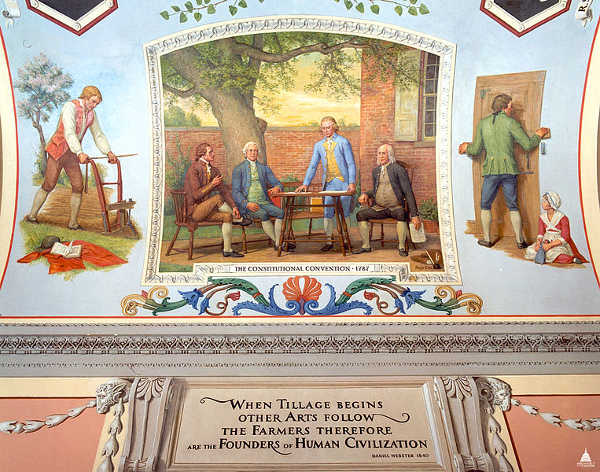

Hence, the convening of this new convention in Philadelphia in 1787 – the Constitutional Convention.

Who were these men, whose genius went into creating a country that thrives to this day? Well, they were certainly not representative of most Americans at the time.

There were 55 delegates; all of them were white and all of them men. A majority were lawyers and wealthy landowners. Most were the type of aristocrats that Alexander had striven to be since first stepping foot on American soil. The average age was 42 years old; meaning 32-year-old Alexander Hamilton was one of the youngest to attend. The oldest man in attendance was 81-year-old Benjamin Franklin.

In theory, the convention had been called only to amend the Articles, not throw them out the window. But on May 30, a man named Edmund Randolph presented a plan to the convention, chiefly formulated by James Madison, that proposed to do just that. The following week or more of debate pretty much established that this convention would walk away not with revised Articles, but a completely new framework.

Throughout these debates, Alexander Hamilton sat quietly on the sidelines – peculiar behavior for a man known for his long speeches. His friends and allies were equally confused. They couldn’t understand why Alexander, usually so vocal about everything, just sat there. Some thought that being so young compared to the other delegates, Hamilton was deferring to their seniority.

In the end, Alexander Hamilton did what he did best. On June 18, 1787, he rose from his seat one afternoon during the debates and began speaking. He spoke, and he spoke, and he spoke some more.

After six hours had passed, Hamilton sat down, probably to a great sigh of relief from the other delegates.

Hamilton would later regret some of the things he said in his speech, but at the time he spoke his ideas with the same wit and energy as he had always done. We have no written transcript of the speech, but James Madison and others did take notes as Hamilton rambled on.

To begin with, Hamilton scoffed at the idea of so much democracy in a national government. Of all the men in that room, Hamilton probably had the lowest opinion of the wisdom of the common people. He had seen angry mobs too many times to have much faith in the masses.

He pointed to the Virginia Plan proposed by James Madison, which gave a lot of power to the people and laughed. “And what even is the Virginia Plan,” he asked, standing and sweating in the hot, stifling room, “but democracy checked by democracy …?” Instead, Hamilton set out his own plan; let’s call it the Hamilton Plan.

Under the Hamilton Plan, the nation would elect a president and a senate.

So far so good, thought most of the delegates.

The president and senate would then have their positions for life, so long as they maintained “good behavior.” Although he didn’t say it, he envisioned that both the president and the men of the Senate would come from the elite of the states – no rabble here, please.

What? A term for life? How is that any different from a monarchy?

In addition to a senate and a president, there would be another legislative body, the House of Representatives. Those men would be elected directly by the people and would serve a term of three years.

Okay, not bad.

And then Alexander Hamilton, in a moment of unusual poor judgement, started to praise England’s form of government.

That was the last straw for many delegates. In the coming years, his political enemies would point to this speech as evidence that Hamilton favored monarchy.

Alexander Hamilton would go on to make several other blunders over the course of his career in politics, but none that persisted as long as his speech at the Constitutional Convention.

Nevertheless, he achieved a level of power and influence that rivaled the president before his eventual murder at the hands of Aaron Burr during that famous duel in 1804.

Antone Pierucci is curator of history at the Riverside County Park and Open Space District and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?