A lone man stalked the elegant cafes along the Avenue de l’Opera in Paris, France. He was ordinary, just one among many out for a stroll along the popular street of cafes. The only thing odd about him, if anyone even took the time to look closely, was that this ordinary man carried a metal lunchbox—like the type used by factory workers.

But like I said, such a detail would only have briefly registered with the occasional passerby.

This lone, completely ordinary man of middle age, carrying a metal lunchbox, turned into the Cafe Terminus and sat at a table.

The waiter arrived and took the man’s order: a beer and a cigar, please. His cigar arrived first, along with a box of matches and an ashtray. Picking one match out of the box, this ordinary man named Emile Henry struck one end of the match.

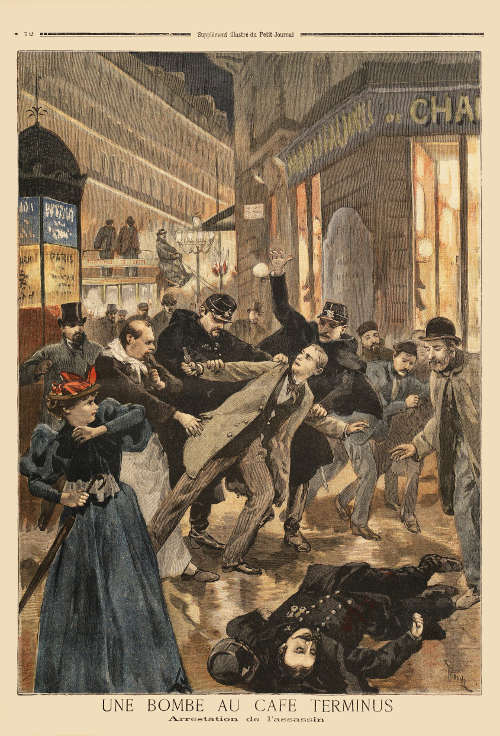

Cupping his other hand in front of the one with the match, Henry shielded the small flame and lit his cigar. Then he discreetly bent down and, with his newly-lit cigar, lit his lunchbox – or rather the bomb inside the lunchbox. Sitting up straight, Henry gathered his hat and ran out of the café just as the windows burst in a spray of glass, wood and shrapnel from his bomb. The ensuing carnage killed one and injured 20. Henry was wrestled to the ground as he tried to escape.

Emile Henry had arguably conducted the first act of modern terrorism.

* * *

Our idea of terrorism crumbled to pieces along with the Twin Towers on Sept. 11, 2001.

Whatever we once associated with acts of terrorism, from then on we would picture only radical religionists.

But I think we are currently witnessing firsthand in our own country that politics and the furor of partisan ideology are potent enough on their own to poison one’s mind and – in extreme cases – bend one’s hand towards terror.

If we were to cast our minds back to Sept. 10, 2001, we might remember that the cry of the terrorist has not always been one of religious fervor, and that those selfsame maniacs have not always come from the Middle East. In fact, we might recall that Western Europe itself has bred its fair share of terrorist movements.

Before radical Islam, for instance, there was the radical ideology of the anarchists.

* * *

Emile Henry was just one of thousands of men and women who proscribed to the beliefs of anarchism.

Developed around the same time as communism, anarchy as a political ideology was really a cluster of many schools of thought, but all of them shared an embittered hatred of government and/or authority of any institutionalized sort.

Anarchists were, you could say, extreme individualists that held the rights of the individual at the same level others held God.

In the earliest manifestations of anarchism, the notion of nonviolence was esteemed just as highly as the divine right of the individual.

But, just as Christianity, which is based on the tenets of love and compassion, became the excuse for such atrocities as the Crusades and Spanish Inquisition, so too did anarchism over time lose its more pacifist tendencies. If anarchists were going to get rid of every sovereign, they began to think, they would have to do it forcibly.

Within a few decades, anarchists had developed the notion of “Propaganda of the Deed,” which was specific political action meant to inspire revolution and further acts of anarchy.

In the early years, these deeds were acts of terrorism that solely targeted policemen and politicians. Things started to change in the 1890s, however, when anarchists began to spread their propaganda through deeds of indiscriminate murder.

One of the first to do that was Emile Henry and his lunchbox bomb. According to Henry, in setting off the bomb in a busy café, he had acted on his belief that “there are no innocent bourgeois.” Here was a man who targeted not a specific person or member of law enforcement, but anyone who happened to be in the café that day.

Anarchists seemed to have been inspired by this and other bloody acts of terrorism. Later that same year as Henry’s café bombing, another anarchist assassinated the president of France. Several years later, the king of Italy was killed.

In North America, politicians looked askance at all the turmoil caused by European anarchists and worried. Oh sure, America had already by then experienced anarchist violence – with the famous Haymarket Riots of 1886 in Chicago being a perfect example – but no high profile targets had yet to be successfully killed.

That all changed on Sept. 6, 1901, in Buffalo, New York when United States President McKinley was shot twice in the stomach by a 28-year old anarchist.

After he was rushed to the nearest doctor – a gynecologist was all they had on hand – McKinley began to recover reasonably well, so well that his vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, set out on a camping trip a few days later.

However, once his wound turned gangrenous, the president quickly faded and in the early hours of Sept. 14, 1901, America’s 25th president – and anarchism’s latest victim – lay cold.

Terrorism is not unique to any one religion, culture or political ideology. It is the manifestation of the basest of human emotions. For decades, the face of terrorism was the faceless European anarchist.

Today, it’s religious radicals. Tomorrow? Who knows?

Antone Pierucci is curator of history at the Riverside County Park and Open Space District and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?