Depending on your own religious inclinations, the idea of saints conjures up different associations.

To some, they imagine comfort, protection, righteousness and concrete evidence of God’s presence in the world. To others, they imagine persecution, dogmatic adherence and clericalism.

Regardless of your views, I think it’s safe to say that many people don’t think of America, when they think of saints.

And yet, there is Elizabeth Ann Seton, the first American-born saint.

Elizabeth Ann Bayley couldn’t have been more American. She was an actual daughter of the American Revolution, having been born in 1774, just two years before the Declaration of Independence was penned.

By marriage and by parentage, she was the fruit of generations of wealthy and influential New Yorkers. Elizabeth’s father, Dr. Richard Bayley, raised her as a good Episcopalian, and she learned the disciplined religious observance characteristic of the Episcopal faith.

At 19, Elizabeth was the belle of New York and she liked it. She soon married William Magee Seton, a wealthy businessman. Over the next several years, the happy couple had five children.

Following in her father’s footsteps, Elizabeth Ann Seton became deeply involved in philanthropic work and in 1797, together with Isabella Graham and other women of elite New York society, she formed the Society for the Relief of Poor Widows with Small Children – the city’s first charitable organization.

Everything went to Hell for Elizabeth when her husband died of tuberculosis and the business failed. Widowed at just 30 and with five children to care for, she was terrified.

While her husband still lived, she had travelled with him to Italy to seek a cure for his ailment. While there, in the capital of the Catholic faith, she observed what she considered the quiet, but deep devotion to God’s will.

She also met some old friends of her husband’s, who were also Catholic, providing her a up-close look at the faith. Although her husband and her left with no cure, Elizabeth herself returned to America with a new interest.

After her husband’s death, against all sense and the wishes of family and friends, Elizabeth converted to Catholicism in March of 1805, one year after her husband’s death.

Herself now a widow with small children, she found it almost impossible to earn a living. Like many of the young women she had helped through the charitable organization, Elizabeth now had no support from her family and friends.

The moment she had converted, she was cast out from society almost entirely. For a time she operated a small school for boys, in order to scrape by, but things were still looking grim.

In early America, and for a century later, anti-Catholic sentiment was rampant. As ardent Protestants, the faithful in America held a deep-seated distrust for Catholics, in part stemming from what they perceived as their following to a distant potentate in Rome.

It didn’t help that Catholicism was so centralized compared to the more regional individuality of American Protestantism. It is easier to ascribe conspiratorial ambitions to an organized group with international reach.

Later in the 1830s, as nativist sentiment in America reached a fever pitch, lurid rumors about sexual slavery and infanticide spurred riots against Catholics in cities like Philadelphia.

For now, Elizabeth only had bigots to deal with. After facing difficulty with her school for boys, she accepted an invitation in 1808 from the priest (later bishop) Louis William Dubourg, president of St. Mary’s College in Baltimore, Maryland. Dubourg wanted Ann to open a school for Catholic girls in that city.

Together with several young women who joined in her work, Elizabeth transported her mission of charity in a new city. Meanwhile, members of the Catholic hierarchy and the Italian friends she had met in Italy, paid for the education of her two sons at Georgetown University.

With her children’s future secured, Elizabeth fulfilled a dream of hers and in 1809 founded a religious community. Seton and the other women she worked with took the oath and became the Sisters of St. Joseph, the first American-based Catholic sisterhood.

A few months later Mother Seton and the sisters moved their home and school to Emmitsburg, Maryland, where they provided free education for the poor girls of the parish.

Until her death in 1821, Mother Seton piloted what many consider the first Catholic parochial school in the United States.

Not all was rosy for Mother Seton. Two of her daughters died of the very disease that had taken her husband and Mother Seton herself continuously struggled with the disease. Ultimately, tuberculosis would claim her too.

Elizabeth Ann Seton’s legacy was legion, including the inspiration for Seton Hall College, which was named after her and remains a school of higher education to this day. She was officially canonized in 1975.

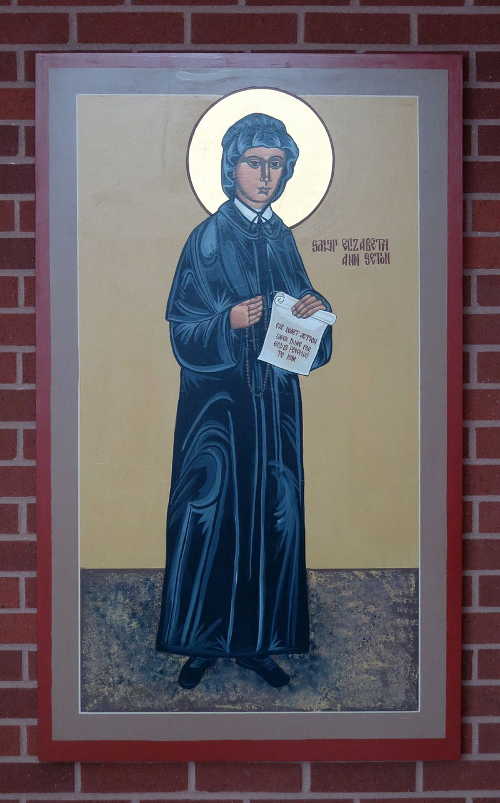

St. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s feast day is Jan. 4, and she is the patron saint of widows. She was the first American born Catholic saint. Often depicted in a voluminous, black dress and bonnet typical of New England at the time, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton certainly looks the part.

Antone Pierucci is curator of history at the Riverside County Park and Open Space District and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?