Health

More people are being affected by drug-induced liver injury (DILI) than ever before, according to a new study in Gastroenterology, the official journal of the American Gastroenterological Association.

This type of liver injury results from the use of certain prescription and over-the-counter medications, as well as dietary supplements, and is among the more challenging forms of liver disease due to its difficulty to predict, diagnose and manage.

Investigators conducted a population-based study in Iceland uncovering 19.1 cases of drug-induced liver injury per 100,000 inhabitants, per year.

These results are significantly higher than the last population-based study of this kind, conducted in France from 1997-2000, which reported 13.9 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, per year.

The most commonly implicated drugs were amoxicillin-clavulante (penicillin used to fight bacteria), azathioprine (an immunosuppressive drug used in organ transplantation and autoimmune diseases) and infliximab (also used to treat autoimmune disease).

“Drug-induced liver injury is not a single, uncommon disease of the general population, but rather a series of rare diseases that occur only in persons who take specific medications,” said Einar S. Björnsson, lead study author from the department of internal medicine, section of gastroenterology and hepatology, National University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland, and faculty of medicine at the University of Iceland.

“Our study identified which medications put patients most at risk for developing liver diseases. With this information, physicians can better monitor and manage patients who are prescribed potentially liver-injuring drugs,” said Björnsson.

The study also showed that drug-induced liver injury was caused by a single prescription medication in 75 percent of cases, by dietary supplements in 16 percent and by multiple agents in 9 percent.

Further, the incidence was similar in women and men, but increased with age; not surprising since the need for medication also increases with age.

Jaundice and other symptoms highly suggestive of liver injury, such as itching, nausea, abdominal discomfort and lethargy, were present in the majority of patients. Most patients had a favorable outcome after receiving care.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

The very system that is meant to protect the body from invasion may be a traitor. These new findings of a study, led by investigators at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC), reveal that infection-fighting white blood cells play a role in activating cancer cells and facilitating their spread to secondary tumors.

This research, published today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation has significant implications for both the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

“We are the first to identify this entirely new way that cancer spreads,” said senior author Dr. Lorenzo Ferri, MUHC director of the Division of Thoracic Surgery and the Upper Gastrointestinal (GI) Cancer Program. “What's equally exciting is medications already exist that are being used for other non-cancer diseases, which may prevent this mechanism of cancer spread or metastasis.”

According to Dr. Ferri, the next steps are to validate if these medicines will work for the prevention and treatment of cancer metastasis, and then to determine the optimal timing and dosing.

Linking infection, inflammation and metastasis

“Our first clue of this association was from our previous research, which showed that severe infection in cancer patients after surgery results in a higher chance that patients will have the cancer return in the form of cancer metastasis,” said Dr. Ferri, who is also an Associate Member of the Rosalind and Morris Goodman Cancer Research Centre and Associate Professor in the Department of Oncology at McGill University. “This led us to investigate the cellular players in the infection, notably neutrophils, the first and most numerous of the white blood cells that are used by the immune system fight off infections.”

Dr. Ferri and his colleagues from McGill University and the University of Calgary used both cultured cells and mouse models of cancer to show that there is a relationship between infection, a white blood cell response (inflammation) and metastasis.

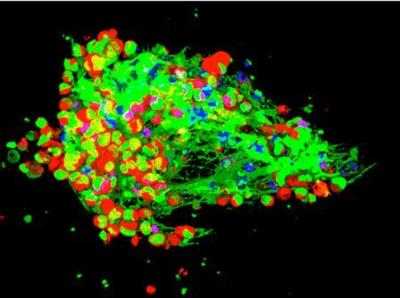

A web-like network called Neutrophils Extracellular Traps (NETs), is produced by white blood cells (neutrophils) in response to an infection and this normally traps and kills invading pathogens, such as bacteria.

“We demonstrated that in the case of infected animals with cancer, the neutrophil web (NETs) also trapped circulating cancer cells,” added Dr. Jonathan Cools-Lartigue, first author of the study, and a PhD student from the LD MacLean Surgical Research Laboratories at McGill University. “Instead of killing the cancer cells, these webs activated the cancer cells and made them more likely to develop secondary tumours, or metastasis.”

No web equals better outcome

The researchers went one step further and showed that breaking down the neutrophil web is achievable by using certain medication.

Furthermore, in mice with cancer, markedly less tumour growth and metastasis occurred after the medication was administered.

This finding was true for a number of different cancer types, suggesting that neutrophil webs may be a common pathway involved in the spreading of many cancers.

“Our study reflects a major change in how we think about cancer progression,” said Dr. Ferri. “And, more importantly, how we can treat it.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?