Health

People infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) can stave off the symptoms of AIDS thanks to drug cocktails that mainly target three enzymes produced by the virus, but resistant strains pop up periodically that threaten to thwart these drug combos.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the National Institutes of Health have instead focused on a fourth protein, Nef, that hijacks host proteins and is essential to HIV's lethality.

The researchers have captured a high-resolution snapshot of Nef bound with a main host protein, and discovered a portion of the host protein that will make a promising target for the next-generation of anti-HIV drugs. By blocking the part of a key host protein to which Nef binds, it may be possible to slow or stop HIV.

“We have imaged the molecular details for the first time,” said structural biologist James H. Hurley, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology. “Having these details in hand puts us in striking distance of designing drugs to block the binding site and, in doing so, block HIV infectivity.”

Hurley, cell biologist Juan Bonifacino of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) of the National Institutes of Health and their colleagues report their findings in a paper published Jan. 28 by the open-access, online journal eLife.

The report comes a month after President Barack Obama pledged to redirect $100 million in the NIH budget to accelerate development of a cure for AIDS, though therapies to halt the symptoms of AIDS will remain necessary for the immediate future, Bonifacino said.

“For many patients, current drug therapies have transformed HIV infection into a chronic condition that doesn't lead to AIDS, but anything we can develop to further interfere with replication and propagation of the virus would help keep it in check until we find a way to completely eliminate the virus from the body,” he said.

HIV hijacks cellular machinery

HIV contains a small number of genes that produce only 15 different proteins, all of which hijack some aspect of immune cells' internal machinery to produce more copies of the virus.

Current anti-AIDS drugs block three HIV enzymes – proteins that transcribe and insert the virus’ genetic material, and snip some of the encoded proteins – but researchers are now looking for drugs that target the other proteins as backups to current therapies. In particular, they are searching for ways to block sites on host proteins to which the virus proteins bind in order to stop HIV. This has to be done without interfering with normal cell function, however.

Nearly 20 years ago, scientists showed that without the protein Nef – short for negative factor – HIV is far less infective. Some patients can live for decades without problems if infected with a Nef-defective virus.

Since then, more details have emerged about Nef's role. HIV enters immune system cells via a receptor called CD4, but once “HIV gets into cells through the CD4 door, it slams the door shut behind itself to prevent unproductive re-infection,” Hurley said.

Scientists aren't sure why HIV slams the door on other viruses, he said, though it may be a way to prevent too many viruses entering the same cell, making the cellular environment less favorable for productive viral replication.

Whatever the reason, the virus prevents further HIV infection by ridding the cell surface of all other CD4 receptors. Nef achieves this by tagging the CD4 receptor so that the cell thinks it is trash and carries it to the cell's incinerator, the lysosome, where it is destroyed.

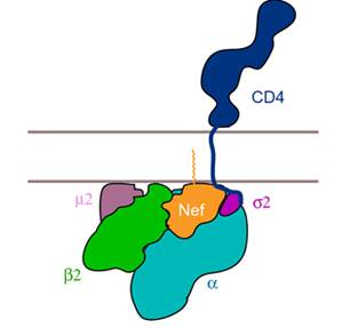

Six years ago, Bonifacino and colleagues found that Nef does this by directly binding to a host protein, AP2, that latches onto a protein called clathrin. This causes the cell membrane to bulge inward and pinch off to form a small membrane bubble that carries attached CD4 receptors to the lysosome for destruction.

“The new high-resolution image reveals a cavity at the site where Nef binds to AP2, that could be a good site for drug targeting,” Bonifacino said.

“This cavity on AP2 is not known to be used by any other host protein, so if we interfere with the cavity we are not going to interfere with any host cell function, only the function of Nef,” he said. “This will inform better searches for inhibitors.”

Hurley cautioned, however, that the research “needs more validation to prove that the cavity is a target. But we are excited because it is a potential target, and these things don't come along every day.”

Taking a snapshot

UC Berkeley scientist Xuefeng “Snow” Ren obtained the high-resolution snapshot of Nef bound to AP2 by crystallizing the proteins and zapping the complex with X-rays. She calculated the 3-D structure from the resulting X-ray diffraction pattern.

She is now at work crystallizing the Nef-AP2 complex bound to the CD4 receptor to look for other possible drug targets on AP2 or CD4 that could prevent Nef from trashing CD4.

Hurley and Bonifacino are primarily interested in the function of adaptors like AP2 – there are at least five known adaptors in human cells – that control intracellular membrane traffic.

“This work was an extension of our work on clathrin adaptors, an opportunity to do something relevant to fighting HIV that was based on the purely basic research we are doing on the sorting of proteins to lysosomes,” Hurley said.

Sang Yoon Park of NICHD is an author of the paper. The work was supported by Grant P50GM082250 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH, the intramural program of the NICHD and the NIH Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program.

Robert Sanders writes for the UC Berkeley News Center.

- Details

- Written by: Robert Sanders

The same kinds of impulsive behavior that lead some people to abuse alcohol and other drugs may also be an important contributor to an unhealthy relationship with food, according to new research from the University of Georgia.

In a paper published recently in the journal Appetite, researchers found that people with impulsive personalities were more likely to report higher levels of food addiction – a compulsive pattern of eating that is similar to drug addiction – and this in turn was associated with obesity.

“The notion of food addiction is a very new one, and one that has generated a lot of interest,” said James MacKillop, the study's principal investigator and associate professor of psychology in UGA's Franklin College of Arts and Sciences. “My lab generally studies alcohol, nicotine and other forms of drug addiction, but we think it's possible to think about impulsivity, food addiction and obesity using some of the same techniques.”

More than one-third of U.S. adults are obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, putting them at greater risk for heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and certain types of cancer.

The estimated annual medical cost of obesity was $147 billion in 2008 U.S. dollars, and obese people pay an average of $1,429 more in medical expenses than those of normal weight.

MacKillop and doctoral students Cara Murphy and Monika Stojek hope that their research will ultimately help physicians and other experts plan treatments and interventions for obese people who have developed an addiction to food, paving the way for a healthier lifestyle.

The study used two different scales, the Yale Food Addiction Scale and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale, to determine levels of food addiction and impulsivity among the 233 participants. Researchers then compared these results with each participant's body mass index, which is used to determine obesity.

“Our study shows that impulsive behavior was not necessarily associated with obesity, but impulsive behaviors can lead to food addiction,” MacKillop said.

That is, just because someone exhibits impulsive behavior does not mean they will become obese, but an increase in certain impulsive behaviors is linked to food addiction, which appeared to be the driving force behind higher BMI in study participants.

These results are among the first forays into the study of addictive eating habits and how they contribute to obesity.

Working with a grant from UGA's Obesity Initiative, MacKillop's team now plans to expand their research by analyzing the brain activity of different individuals as they make decisions about food.

The contemporary food industry has created a wide array of eating options, and foods that are high in fat, sodium, sugar and other flavorful additives and appear to produce cravings much like illicit drugs, MacKillop said. Now they will work to see how those intense cravings might play a role in the development of obesity.

“Modern neuroscience has helped us understand how substances like drugs and alcohol co-opt areas of the brain that evolved to release dopamine and create a sense of happiness or satisfaction,” he said. “And now we realize that certain types of food also hijack these brain circuits and lay the foundation for compulsive eating habits that are similar to drug addiction.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?