Health

Patients who received an implantable heart defibrillator in everyday practice had survival benefits on par with those who received the same devices in carefully controlled clinical trials, according to a new study that highlights the value of defibrillators in typical medical settings.

Led by the Duke Clinical Research Institute and published Jan. 2 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the study used data from a large national Medicare registry to assess the survival of patients receiving defibrillators, which are commonly used to prevent sudden cardiac death.

Because clinical trial participants tend to receive more meticulous care while also being healthier than patients seen in clinical practice, the actual benefits of new drugs and medical devices can be less positive than initially reported.

Not so for the defibrillators, at least when comparing patients with similar characteristics in both the clinical trials and real-world practice.

“Many people question how the results of clinical trials apply to patients in routine practice,” said lead author Sana M. Al-Khatib, M.D., MHS, an electrophysiologist and member of the Duke Clinical Research Institute. “We showed that patients in real-world practice who receive a defibrillator but who are most likely not monitored at the same level provided in clinical trials have similar survival outcomes compared to patients who received a defibrillator in the clinical trials.”

“This study demonstrated the real-world applicability of the results of recent randomized clinical trials,” said Alice Mascette, M.D., of the NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have been lifesavers for people with a history of cardiac arrest or heart failure.

The devices, small electrical units implanted in the chest with wires that lead into the heart, send an electronic pulse when the heart stops beating to reestablish a normal rhythm.

To monitor treatment patterns, effectiveness and safety of ICDs among Medicare patients, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services mandated that data on all Medicare patients receiving a primary prevention ICD be entered into a national registry.

In response to this mandate, a national ICD Registry has been collecting data from hospitals performing implantations since 2005. The Duke-led research group used data from that registry to compare more than 5,300 real-world patients against more than 1,500 patients who had enrolled in two large clinical trials of ICD devices.

Al-Khatib said the patients who were included in the analysis were selected to closely resemble the patients who participated in the clinical trials, with much older and sicker patients in the registry excluded.

Both groups – study participants who received an ICD and ordinary recipients – had similar two-year and three-year survival rates. Ordinary recipients had better survival than patients in the clinical trial who did not receive an ICD. These findings were true for Medicare and non-Medicare patients.

By comparing similar populations, the researchers were able to address the concern that outcomes reported in clinical trials are overly optimistic because patients receive extraordinary care.

“We know from previous studies that many patients in real-world clinical settings don’t receive the follow-up care that is recommended after the device is implanted,” Al-Khatib said. She said doctors who participate in clinical trials also tend to be highly skilled specialists who do hundreds of the implantation surgeries, while physicians in ordinary practice may be less proficient. Studies have shown that patients have more complications when their doctors have less experience with a procedure.

Al-Khatib said the study had a limitation that could warrant additional examination. By eliminating Medicare patients who were appreciably older and sicker than those who enrolled in the clinical trials, the researchers were unable to determine how all patients seen in real-world practice compare to study participants.

“That is in an issue, and the only way to get at that is to randomly assign such patients to either receive an ICD or not in a clinical trial,” Al-Khatib said. “Even without those data, however, our study gives patients and their health care providers reassurance that what we have been doing in clinical practice has been helpful, and is improving patient outcomes. Our findings support the continued use of this life saving therapy in clinical practice.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor

While legions of medical researchers have been looking to understand the genetic basis of disease and how mutations may affect human health, a group of biomedical researchers at UC Santa Barbara is studying the metabolism of cells and their surrounding tissue, to ferret out ways in which certain diseases begin.

This approach, which includes computer modeling, can be applied to Type 2 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and neurodegenerative diseases, among others.

Scientists at UCSB have published groundbreaking results of a study of Type 2 diabetes that point to changes in cellular metabolism as the triggering factor for the disease, rather than genetic predisposition.

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic condition in which blood sugar or glucose levels are high. It affects a large and growing segment of the human population, especially among the obese. The team of scientists expects the discovery to become a basis for efforts to prevent and cure this disease.

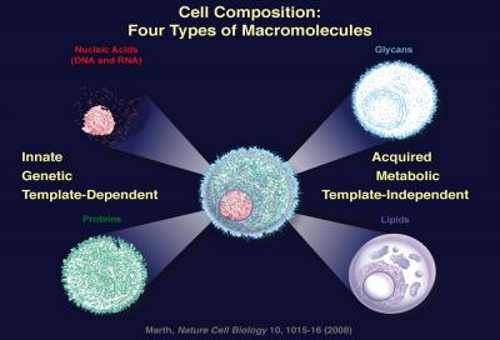

The current work is based on a previous major finding by UCSB’s Jamey Marth, who determined the identity of the molecular building blocks needed in constructing the four types of macromolecules of all cells when he was based at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in La Jolla in 2008.

These include the innate, genetic macromolecules, such as nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) and their encoded proteins, and the acquired metabolic macromolecules known as glycans and lipids.

Marth is a professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology and the Biomolecular Science and Engineering Program; and holds the John Carbon Chair in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the Duncan and Suzanne Mellichamp Chair in Systems Biology. He is also a professor with the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute in La Jolla.

“By studying the four types of components that make up the cell, we can, for the first time, begin to understand what causes many of the common grievous diseases that exist in the absence of definable genetic variation, but, instead, are due to environmental and metabolic alterations of our cells,” said Marth. UCSB is the only institution studying these four types of molecules in the cells while also using computational modeling to determine their functions in health and disease, according to Marth.

The new study, published in the December 27 issue of PLOS ONE, relies on computational systems biology modeling to understand the pathogenesis of Type 2 diabetes.

“Even in the post-genomic era, after the human genome has been sequenced, we’re beginning to realize that diseases aren’t always in our genes – that the environment is playing a major role in many of the common diseases,” said Marth.

Normally, beta cells in the pancreas sense a rise in blood sugar and then secrete insulin to regulate blood glucose levels.

But in Type 2 diabetes, the beta cells fail to execute this important function and blood sugar rises, a trend that can reach life-threatening levels.

The researchers identified a “tipping point,” or metabolic threshold, that when crossed results in the failure of beta cells to adequately sense glucose in order to properly secrete insulin.

Obesity has long been linked to Type 2 diabetes, but the cellular origin of the disease due to beta cell failure has not been described until now.

“In obesity there’s a lot of fat in the system,” said Marth. “When the cell is exposed to high levels of fat or lipids, this mechanism starts, and that’s how environment plays a role, among large segments of the population bearing ‘normal’ genetic variation. We’re trying to understand what actually causes disease, which is defined as cellular dysfunction. Once we understand what causes disease we can make a difference by devising more rational and effective preventative and therapeutic approaches.”

The research was based on a unique approach. “This project illustrates the power of systems biology; namely, how a network perspective combined with computational modeling can shed new light on biophysical circuits, such as this beta-cell glucose transport system,” said co-author Frank Doyle. “It cannot be done by molecular biology alone, nor computational modeling alone; rather, it requires the uniquely interdisciplinary approach that is second-nature here at UCSB.”

Doyle is associate dean for research of the College of Engineering; director of UCSB’s Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies; professor of chemical engineering; and the Mellichamp Chair in Process Control.

“We are excited to bring our 20 years of expertise on Type 1 diabetes and systems biology methods to look at the networks responsible for the onset of Type 2 diabetes,” said Doyle.

According to the American Diabetes Association, 8.3 percent of the U.S. population has diabetes. The disease can lead to nerve loss, blindness, and death.

The first author of the paper is Camilla Luni, who was a UCSB postdoctoral researcher at the time of the study, and is now with the University of Padova, in Italy.

The research was funded by a grant from the U.S. Army Research Office to UCSB’s Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies, and a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?