News

- Details

- Written by: Elizabeth Larson

Dogs available for adoption this week include mixes of Alaskan husky, American blue heeler, Anatolian shepherd, Australian shepherd, border collie, German shepherd, Great Pyrenees, Labrador retriever, pit bull, Queensland heeler, Rottweiler, shepherd and terrier.

Dogs that are adopted from Lake County Animal Care and Control are either neutered or spayed, microchipped and, if old enough, given a rabies shot and county license before being released to their new owner. License fees do not apply to residents of the cities of Lakeport or Clearlake.

Those dogs and the others shown on this page at the Lake County Animal Care and Control shelter have been cleared for adoption.

Call Lake County Animal Care and Control at 707-263-0278 or visit the shelter online for information on visiting or adopting.

The shelter is located at 4949 Helbush in Lakeport.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

Climate change is shifting the zones where plants grow – here’s what that could mean for your garden

- Details

- Written by: Matt Kasson, West Virginia University

With the arrival of spring in North America, many people are gravitating to the gardening and landscaping section of home improvement stores, where displays are overstocked with eye-catching seed packs and benches are filled with potted annuals and perennials.

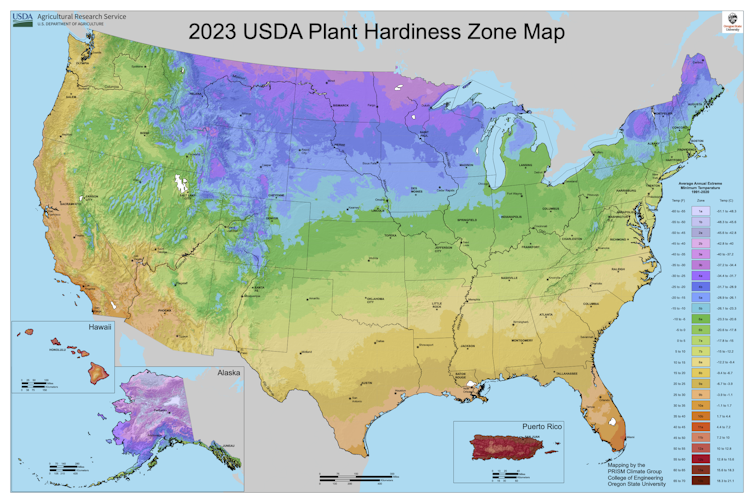

But some plants that once thrived in your yard may not flourish there now. To understand why, look to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s recent update of its plant hardiness zone map, which has long helped gardeners and growers figure out which plants are most likely to thrive in a given location.

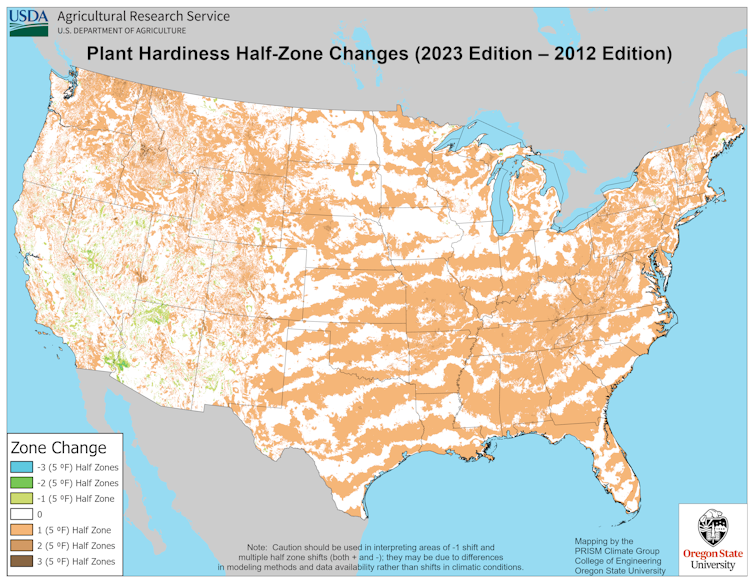

Comparing the 2023 map to the previous version from 2012 clearly shows that as climate change warms the Earth, plant hardiness zones are shifting northward. On average, the coldest days of winter in our current climate, based on temperature records from 1991 through 2020, are 5 degrees Fahrenheit (2.8 Celsius) warmer than they were between 1976 and 2005.

In some areas, including the central Appalachians, northern New England and north central Idaho, winter temperatures have warmed by 1.5 hardiness zones – 15 degrees F (8.3 C) – over the same 30-year window. This warming changes the zones in which plants, whether annual or perennial, will ultimately succeed in a climate on the move.

As a plant pathologist, I have devoted my career to understanding and addressing plant health issues. Many stresses not only shorten the lives of plants, but also affect their growth and productivity.

I am also a gardener who has seen firsthand how warming temperatures, pests and disease affect my annual harvest. By understanding climate change impacts on plant communities, you can help your garden reach its full potential in a warming world.

Hotter summers, warmer winters

There’s no question that the temperature trend is upward. From 2014 through 2023, the world experienced the 10 hottest summers ever recorded in 174 years of climate data. Just a few months of sweltering, unrelenting heat can significantly affect plant health, especially cool-season garden crops like broccoli, carrots, radishes and kale.

Winters are also warming, and this matters for plants. The USDA defines plant hardiness zones based on the coldest average annual temperature in winter at a given location. Each zone represents a 10-degree F range, with zones numbered from 1 (coldest) to 13 (warmest). Zones are divided into 5-degree F half zones, which are lettered “a” (northern) or “b” (southern).

For example, the coldest hardiness zone in the lower 48 states on the new map, 3a, covers small pockets in the northernmost parts of Minnesota and has winter extreme temperatures of -40 F to -35 F. The warmest zone, 11b, is in Key West, Florida, where the coldest annual lows range from 45 F to 50 F.

On the 2012 map, northern Minnesota had a much more extensive and continuous zone 3a. North Dakota also had areas designated in this same zone, but those regions now have shifted completely into Canada. Zone 10b once covered the southern tip of mainland Florida, including Miami and Fort Lauderdale, but has now been pushed northward by a rapidly encroaching zone 11a.

Many people buy seeds or seedlings without thinking about hardiness zones, planting dates or disease risks. But when plants have to contend with temperature shifts, heat stress and disease, they will eventually struggle to survive in areas where they once thrived.

Successful gardening is still possible, though. Here are some things to consider before you plant:

Annuals versus perennials

Hardiness zones matter far less for annual plants, which germinate, flower and die in a single growing season, than for perennial plants that last for several years. Annuals typically avoid the lethal winter temperatures that define plant hardiness zones.

In fact, most annual seed packs don’t even list the plants’ hardiness zones. Instead, they provide sowing date guidelines by geographic region. It’s still important to follow those dates, which help ensure that frost-tender crops are not planted too early and that cool-season crops are not harvested too late in the year.

User-friendly perennials have broad hardiness zones

Many perennials can grow across wide temperature ranges. For example, hardy fig and hardy kiwifruit grow well in zones 4-8, an area that includes most of the Northeast, Midwest and Plains states. Raspberries are hardy in zones 3-9, and blackberries are hardy in zones 5-9. This eliminates a lot of guesswork for most gardeners, since a majority of U.S. states are dominated by two or more of these zones.

Nevertheless, it’s important to pay attention to plant tags to avoid selecting a variety or cultivar with a restricted hardiness zone over another with greater flexibility. Also, pay attention to instructions about proper sun exposure and planting dates after the last frost in your area.

Fruit trees are sensitive to temperature fluctuations

Fruit trees have two parts, the rootstock and the scion wood, that are grafted together to form a single tree. Rootstocks, which consist mainly of a root system, determine the tree’s size, timing of flowering and tolerance of soil-dwelling pests and pathogens. Scion wood, which supports the flowers and fruit, determines the fruit variety.

Most commercially available fruit trees can tolerate a wide range of hardiness zones. However, stone fruits like peaches, plums and cherries are more sensitive to temperature fluctuations within those zones – particularly abrupt swings in winter temperatures that create unpredictable freeze-thaw events.

These seesaw weather episodes affect all types of fruit trees, but stone fruits appear to be more susceptible, possibly because they flower earlier in spring, have fewer hardy rootstock options, or have bark characteristics that make them more vulnerable to winter injury.

Perennial plants’ hardiness increases through the seasons in a process called hardening off, which conditions them for harsher temperatures, moisture loss in sun and wind, and full sun exposure. But a too-sudden autumn temperature drop can cause plants to die back in winter, an event known as winter kill. Similarly, a sudden spring temperature spike can lead to premature flowering and subsequent frost kill.

Pests are moving north too

Plants aren’t the only organisms constrained by temperature. With milder winters, southern insect pests and plant pathogens are expanding their ranges northward.

One example is Southern blight, a stem and root rot disease that affects 500 plant species and is caused by a fungus, Agroathelia rolfsii. It’s often thought of as affecting hot Southern gardens, but has become more commonplace recently in the Northeast U.S. on tomatoes, pumpkins and squash, and other crops, including apples in Pennsylvania.

Other plant pathogens may take advantage of milder winter temperatures, which leads to prolonged saturation of soils instead of freezing. Both plants and microbes are less active when soil is frozen, but in wet soil, microbes have an opportunity to colonize dormant perennial plant roots, leading to more disease.

It can be challenging to accept that climate change is stressing some of your garden favorites, but there are thousands of varieties of plants to suit both your interests and your hardiness zone. Growing plants is an opportunity to admire their flexibility and the features that enable many of them to thrive in a world of change.![]()

Matt Kasson, Associate Professor of Mycology and Plant Pathology, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Details

- Written by: Robert Sanders

BERKELEY, Calif. — Texans have long endured scorching summer temperatures, so a global warming increase of about 3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 Celsius) might not sound like much to worry about.

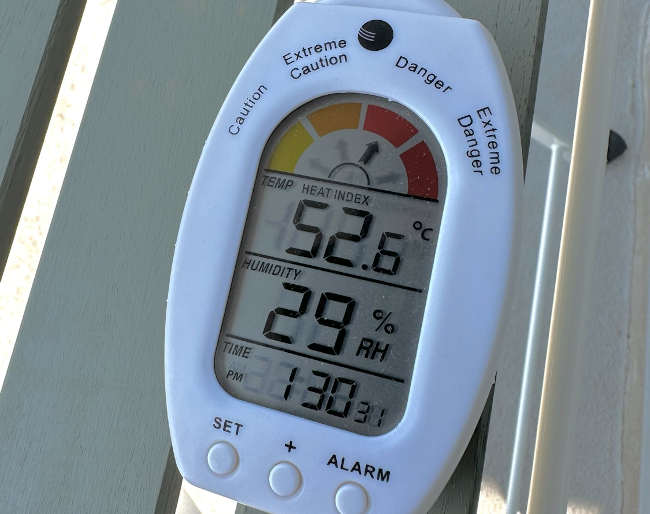

But a new study concludes that the heat index — essentially how hot it really feels — has increased much faster in Texas than has the measured temperature: about three times faster.

That means that on some extreme days, what the temperature feels like is between 8 and 11 F (5 to 6 C) hotter than it would without climate change.

The study, using Texas data from June, July and August of 2023, highlights a problem with communicating the dangers of rising temperatures to the public. The temperature alone does not accurately reflect the heat stress people feel.

Even the heat index itself, which takes into account the relative humidity and thus the capacity to cool off by sweating, gives a conservative estimate of heat stress, according to study author David Romps, a professor of earth and planetary science at the University of California, Berkeley.

In 2022, Romps co-authored a paper pointing out that the way most government agencies calculate the heat index is inaccurate when dealing with the temperature and humidity extremes we're seeing today. This leads people to underestimate their chances of suffering hyperthermia on the hottest days and of their chances of dying.

Texas is not an outlier. Recently, Arizona's most populous county, covering most of Phoenix, reported that heat-associated deaths last year were 50% higher than in 2022, rising from 425 in 2022 to 645 in 2023. Two-thirds of Maricopa County’s heat-related deaths in 2023 were of people 50 years or older, and 71% occurred on days when the National Weather Service had issued an excessive heat warning, according to the Associated Press.

"I mean, the obvious thing to do is to cease additional warming, because this is not going to get better unless we stop burning fossil fuels," Romps said. "That's message No. 1, without doubt. We have only one direction we can really be taking the planet's average temperature, and that's up. And that's through additional burning of fossil fuels. So that's gotta stop and stop fast."

The reason that it feels much hotter than you'd expect from the increase in ambient temperature alone is that global warming is affecting the interplay between humidity and temperature, he said. In the past, relative humidity typically dropped when the temperature increased, allowing the body to sweat more and thus feel more comfortable.

But with climate change, the relative humidity remains about constant as the temperature increases, which reduces the effectiveness of sweating to cool the body.

To deal with the irreversible temperature increases we already experience, people need to take precautions to avoid hyperthermia, Romps said. He advised that, for those in extreme heat situations and unable to take advantage of air conditioning, "you can use shade and water as your friends.

"You can coat yourself in water. Get a wet rag, run it under the faucet, get your skin wet and get in front of a fan. As long as you are drinking enough water and you can keep that skin wetted in front of the fan, you're doing a good thing for yourself."

Romps' study was published March 15 in the journal Environmental Research Letters (ERL).

It's the humidity

Romps, an atmospheric physicist, got interested several years ago in how the human body responds to global warming's increased temperatures.

Although the heat index, defined in 1979, is based on the physiological stresses induced by heat and humidity, he noted that the calculations of the heat index did not extend to the extremes of heat and humidity experienced today.

Romps and graduate student and now postdoctoral fellow Yi-Chuan Lu extended the calculation of the heat index to all combinations of temperature and humidity, enabling its use in even the most extreme heat waves, like those that buffeted Texas in the summer of 2023.

Over the decades, the nation's major weather forecaster, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service, has dealt with the lack of calculated values for high heat and humidity by extrapolating from the known values. Romps and Lu found, however, that the commonly used extrapolation falls far short when conditions of temperature and humidity are extreme.

Although the heat index has now been calculated for all conditions using the underlying physiological model, those values have not yet been adopted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA.

After Lu spent a sweltering summer in Texas last year, Romps decided to take the state as a case study to determine how global warming has affected the perceived heat stress represented by the corrected heat index.

“I picked Texas because I had seen some high heat index values there that made me think, OK, this is a state that this summer is probably experiencing combinations of heat and humidity that are not being captured properly by NOAA’s approximation to the heat index,” he said.

He found that, while temperatures peaked at various places and times around the state last summer, one place, Houston’s Ellington Airport, stood out. On July 23, 2023, he calculated that the heat index was 75 C, or 167 F. Global warming accounted for 12 F (6 C) of that heat index, he said.

“It sounds completely insane,” Romps said. “It’s beyond the physiological capacity of a young, healthy person to maintain a standard core temperature. We think it’s hyperthermic, but survivable.”

The fact that people can survive such temperatures is a testament to the power of evaporative cooling to cool the body, though intense sweating requires the heart to pump more blood to the skin to shed heat, which is part of heat stress.

In a 2023 paper, Romps and Lu argued that what many have referred to as the maximum survivable temperature, a wet bulb temperature of 35 C (equivalent to a skin temperature when sweating of 95 F, close to the average person’s core body temperature), would actually rarely lead to death in a young and healthy adult, though it would cause hyperthermia.

The wet bulb temperature is what a thermometer measures when a wet rag is wrapped around it, so it takes account of the cooling effects of sweat.

"Heat index is very much like the wet bulb thermometer, only it adds the metabolic heat that a human has that a thermometer does not have," Romps said. "We think if you kept your skin wet and you were exposed to 167 degrees, even though we're approaching something like a setting on the oven, you'd still be alive. Definitely not happy. But alive."

While the current study didn't try to predict when, in the future, heat waves in Texas might generate a heat index high enough to make everyone hyperthermic, "we can see that there are times when people are getting pushed in that direction," he said. "It's not terribly far off."

Romps plans to look at other regions in light of the improved heat index scale he and Lu have proposed and expects to find similar trends.

"If humanity goes ahead and burns the fossil fuel available to it, then it is conceivable that half of Earth's population would be exposed to unavoidably hyperthermic conditions, even for young, healthy adults," Romps said. "People who aren't young and healthy would be suffering even more, as would people who are laboring or are out in the sun — all of them would be suffering potentially life-threatening levels of heat stress."

Robert Sanders writes for the UC Berkeley News Center.

- Details

- Written by: NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION

Three crew members including NASA astronaut Tracy C. Dyson successfully launched at 8:36 a.m. EDT Saturday from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to the International Space Station.

Dyson, along with her crewmates Roscosmos cosmonaut Oleg Novitskiy and spaceflight participant Marina Vasilevskaya of Belarus, will dock to the space station’s Prichal module about 11:09 a.m. on Monday, March 25, on the Soyuz MS-25 spacecraft.

Docking coverage will begin at 10:15 a.m. on NASA+, NASA Television, the NASA app, YouTube, and the agency’s website. NASA also will air coverage, starting at 1:15 p.m., of the crew welcome ceremony on NASA+ once they are aboard the orbital outpost. Learn how to stream NASA TV through a variety of platforms including social media.

When the hatches between the station and the Soyuz open about 1:40 p.m., the new crew members will join NASA astronauts Loral O’Hara, Matthew Dominick, Mike Barratt, and Jeanette Epps, as well as Roscosmos cosmonauts Oleg Kononenko, Nikolai Chub, and Alexander Grebenkin, already living and working aboard the space station.

Novitskiy and Vasilevskaya will be aboard the station for 12 days, before providing the ride home for O’Hara on Saturday, April 6, aboard Soyuz MS-24 for a parachute-assisted landing on steppe of Kazakhstan.

Dyson will spend six months aboard the station as an Expedition 70 and 71 flight engineer, returning to Earth in September with Oleg Kononenko and Nikolai Chub of Roscosmos, who will complete a year-long mission on the laboratory.

This will be the third spaceflight for Dyson, the fourth for Novitskiy, and the first for Vasilevskaya.

Learn more about space station activities at https://www.nasa.gov/station.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?