Opinion

It’s Women’s History Month, and it’s not your fault if you didn’t know that.

The tradition started in 1981, when Congress established the second week of March as Women’s History Week. In 1987 they expanded it to a month and every year since, they’ve passed a resolution on it, and the president has issued a proclamation. And yes, he did so this year.

The only sign of it here was on March 8, when Lake County poet laureate Sandra Wade held a reading for International Women’s Day a Redbud Library and urged teachers to give students credit for attending.

OK, we’re not Sonoma County, where the National Women’s History Project started in 1980 and persuaded Congress to pay attention. Their impetus was noticing that only 3 percent of textbook content was about women.

Three percent. It is to laugh, scornfully. Anyone who’s ever watched Western movies knows the nation’s history, to say nothing of the world, is simply teeming with women.

And so are Lake County’s past and present. We’ve had women county supervisors before Denise Rushing. Louise Nan’s superintendent of Konocti Unified School District. A woman started this publication you’re reading.

Dozens, maybe hundreds, of women run our businesses, head political committees, provide health care at all levels, keep volunteer groups running, and lovingly fill that traditional woman’s job, teaching.

Shelby Posada runs the Arts Council, Melissa Fulton runs the Chamber of Commerce. Could you ask for a broader range?

Native women were here when the pioneer families arrived, and today some of them are running things in their tribes. Tracey Avila chairs the Robinson Rancheria Tribal Council. Irenia Quitiquit is Robinson’s environmental director.

(It’s just as well I've only been here four years and don’t know that many people or you’d be getting a very long list of names.)

So – why don’t we celebrate Women’s History Month and the many achievements of our friends and neighbors?

Don’t we care? Or are we just too busy doing today’s work?

Too busy is my guess. So how about we give ourselves a break from how much we are doing to notice what we have done?

And how about sending us a few words on your own favorite piece of women’s history? Mine’s that Mom riveted airplane wings during World War II. Then she made me take typing.

Watch a movie:

– North Country: Based on a real story, stars de-glammed Charlize Theron as one of a handful of women working in the Minnesota iron mines. Forced to labor under sexist conditions, she and her female colleagues fight the relentless harassment of their male co-workers and bring the first class action suit for sexual harassment.

– Iron Jawed Angels (history): From 1912 to 1920, a group of fiery young suffragettes led by Alice Paul (Hilary Swank) and Lucy Burns (Frances O'Connor) band together to wheedle the United States into adapting a Constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote. Their efforts incur the wrath of President Woodrow Wilson (Bob Gunton) and anger other suffragette leaders (Anjelica Huston and Lois Smith). Not a pretty picture.

– Calendar Girls: Based on a true story. These English women are resilient, resourceful and refined. They're also about to shock the residents of their little town. When one of their own discovers her husband has cancer and needs treatment, the group decides to put out their yearly calendar to raise money for the local cancer center. But instead of the usual Yorkshire dales, they'll grace the pages in the nude.

–Little Miss Sunshine is fiction, but has great insight. It gives us pudgy young Olive (Abigail Breslin), obsessed with beauty pageants, a blessedly sane mother (Toni Colette) who tells her it’s OK to be fat, a twitty father (Greg Kinnear) who redeems himself when he’s horrified by the pageant’s other contestants, all tarted up as premature sex objects. Also, it’s very funny, but rated R, in part for the wonderful Alan Arkin’s foul mouth.

Read a book:

– Inés of My Soul, Isabel Allende, 2006. The Chilean author brings her magic realism to an historic novel, the story of Ines Suarez, who left Spain in the 16th century to find her husband and wound up co-founding a New World nation.

– The Yellow Wallpaper, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1892, fiction. What to do with a depressed wife? This doctor husband thinks he knows, but it’s a prescription from hell.

– Writing a Woman’s Life, Carolyn G. Heilbrun, 1988, non-fiction. Great introduction to the historic treatment of women writers, and to rewriting your own life, if it needs that.

– And now for something really light, but crammed with early 20th century history: Laurie R. King’s mystery series based on the premise the retired Sherlock Holmes meets a much, much, younger woman, Mary Russell, who becomes his detecting partner and wife. Start anywhere. You’ll catch up.

E-mail Sophie Annan Jensen at

{mos_sb_discuss:5}

- Details

- Written by: Sophie Annan Jensen

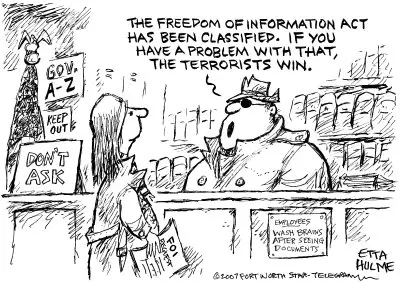

These are strange times for people who advocate for open government. On one hand, technological changes appear to make information about government more easily available than ever before. We live in a radically changed media environment, in which news about government misconduct seems to reach our televisions instantaneously. And if we look around the world, we see an extraordinary spread of laws like the U.S. Freedom of Information Act. Over 70 countries now have FOI laws, most adopted in the last decade.

And yet we seem to be more concerned with government secrecy than ever before. Indeed, some people claim that secrecy today is the worst in decades. How can both of these stories be true?

It might help to recognize that we are in the middle of an intense, global battle over the principle of governmental openness. In the heat of battle, there's a temptation to employ overheated rhetoric. The truth is that the idea of transparency has gained a lot of ground over the last 20 years. This is evident in the spread of FOI laws, and the number of citizens who say that open government is an important value.

Nonetheless, there are serious challenges to openness. One is executive pushback – the determination of political leaders to reverse laws or policies that guarantee openness. As pressure for openness mounts, this countervailing pressure also intensifies. Of course, we've seen a classic case of pushback in United States, where the Bush administration waged a campaign against openness even before the 9/11 attacks. The administration tightened rules governing the Freedom of Information Act and policies on access to presidential records, among other measures.

However, pushback isn't unique to the United States. The British government led by Tony Blair was elected on a promise to introduce a Freedom of Information Act in 1997, but took eight years to put it into force. The new law was in operation for little more than a year when the Blair government announced substantial fee hikes that could gut the law. The Indian government also adopted a Freedom of Information law in 2005, but within months senior officials were pushing for restrictions. A wave of protests – and hunger strikes – deterred Indian leaders from introducing new limits.

Such struggles will continue in the years ahead. Some advocates argue that FOI laws eventually introduce a "culture of openness" in government – but the evidence tends to support a more hardheaded view. As a Canadian politician once said, the struggle over access to information is ultimately a struggle for political power. A well-organized community of stakeholders, including journalists and public interest groups, is essential to make rules about openness stick in the long run.

Executive pushback isn't the only challenge. The very structure of government is also being transformed, often in ways that undermine openness. One obvious example is the growing role of contractors in performing government functions. A 2006 study estimated that almost 8 million people work for federal government contractors – four times the size of the regular government workforce. As we've seen in Iraq, contractors now perform defense and intelligence tasks that we once thought belonged to government alone.

The problem? Most often, contractors aren't affected by FOI laws, so that internal documents about the use of money or power can't be accessed. Indeed, it may be difficult to obtain even the contract itself, which explains what contractors have promised to do, and how much they will be paid. Around the world, battles for access to government contracts are commonplace.

The structure of government is also being changed in more subtle ways. Since 9/11, we've all been reminded of the need to make difficult tradeoffs between security and openness. Less easily seen are the changes in the defense, intelligence, and policing sectors. Government agencies in different states (and different countries) are linking together more tightly, forming networks aimed at improving collective security. This is an admirable goal. But governments often agree to information-sharing agreements that allow inter-governmental confidentiality to trump FOI laws. OK as long as the network performs well – but bad news when the network fouls up, and journalists or citizens try to find out why.

Another subtle but important change: the growing role of international organizations. We live in a globalized economy, superintended by important institutions such as the World Trade Organization (which referees trade disputes), the International Monetary Fund (which monitors governments' economy policies), or the lesser-known ICANN (which rules the internet). Decisions made by organizations such as these affect the well-being of millions of citizens – but they are not required to comply with the transparency rules that we've imposed on national, state and local governments.

Are we making headway on governmental transparency? Frankly, it's too early to tell. The idea of transparency had gained ground. But it's not yet clear whether we will find ways of tailoring openness rules (like FOI laws) to fit new structures of governance. And we can expect political leaders to continue pushing back, especially as their capacity to control the outflow of government information is challenged more directly.

It's a long road ahead. But it's a road we must follow, if we want to protect the ideal of an open, vibrant democracy.

Alasdair Roberts is a professor of public administration at the Maxwell School of Syracuse University. His 2006 book, "Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age," recently won awards from the National Academy of Public Administration and the American Society for Public Administration. His Web site is www.aroberts.us.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?