Opinion

When I asked one of my classmates how he felt about the classification of government information, his response was as terse as it was disappointing. "I don't," he said.

Ask a student you see walking to a class at any college campus in America. The responses rarely vary.

The iPod Generation, with its sleek camera phones and on-demand online news, has all too often simply forgotten about the dirty little secrets that those we empower to run our lives and spend our money hide from us on a daily basis.

We skate across the surface of today's 24-hour news cycle, across the icy layer of the superficial and the celebrity that dominates today’s programming.

So how can anyone blame us?

We are, as the cliché goes, what we eat. As the news becomes increasingly soft and profit-oriented, healthy choices become more and more scarce.

Can I or any other transparency advocate blame a generation choosing from the journalistic equivalent of McDonalds for their unhealthy diet? Logic tells me I must answer no.

Had I never broken through that ice and into the debate room during high school, I, too, might never have discovered the cold waters that lie beneath the surface.

Once I did, the truth was as shocking as any plunge into a wintry lake.

Hundreds of detainees held without charge or due process in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; torture in secret prisons from North Africa to the Middle East to Eastern Europe; illegal wiretapping of American citizens. Every story read like the topic of a high-adrenaline bestseller ready to fall off bookshelves at a Borders or Barnes & Noble near me.

But the stories were true. And the deeper I dove, as I arrived at college and began volunteering at the Freedom of Information Center, the more unbelievable, shocking truths I discovered.

A U.S. government report saying the Iraq War has significantly increased the threat of terrorism, not quelled it; Iraqi insurgents who not only were financially self-sufficient, but even earned enough money to fund other terrorists around the world: These kinds of truths made me stare dumbly at my flat new laptop’s screen.

They underscore the necessity of a national dialogue about open government and transparency like Sunshine Week.

Now that I have seen the shadowy world beneath that layer of ice, I wonder how anyone could simply ignore the injustices our votes enable and tax dollars bankroll.

But I don’t wonder long.

I remember the words of the late President Reagan, who famously classified his grades after taking the oath of office: "all you knew is what I told you."

I remembered what I learned in history class: how he had neglected to mention his decision to sell arms to Iran and send the profits to anti-communist guerrillas in Nicaragua.

I remembered my generation, entirely too young to remember the lesson of the famous Iran-Contra Affair and like every generation, probably could have paid closer attention during American History.

When I think about how little my generation knows about the indignities of our times, I have to forgive them.

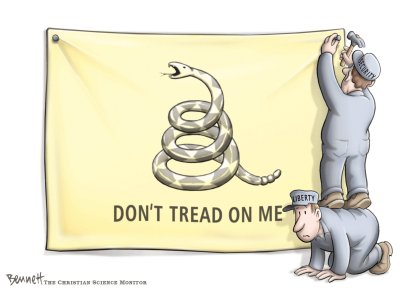

Instead of learning from a young age not to trust our politicians' power to create secrets, we went ice-skating.

Matt Velker is a student at the University of Missouri-Columbia, studying Journalism and Political Science. He can be reached at

{mos_sb_discuss:4}

- Details

- Written by: Editor

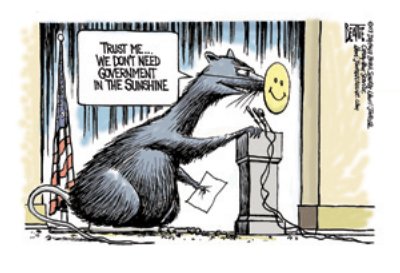

Freedom of Information in Britain is more like a candle flame than the sunshine laws familiar to Americans. Yet despite this country’s late arrival to open government legislation, the British Press are ditching their traditional skepticism and banding together to save our nascent FOI law from imminent destruction. Perhaps we might even start our own "Candle Week."

Britain was one of the last parliamentary societies to pass an FOI law and had the longest lead-in time of any country (five years) before it came into force on Jan. 1, 2005. This country does not have open public records or open meetings laws that mandate the transparent operation of government, so Freedom of Information is one of the only ways to uncover what public officials are doing with public money. In addition, court records are not considered "public" despite being paid for by the taxpayer, so that stream of information – so essential to the American reporter – is restricted. Even so, Prime Minister Tony Blair has lost his enthusiasm for open government after 10 years in power. Under the guise of "cost savings+ our 2-year-old law is about to be gutted.

A consultation ended last week on government proposals that would radically alter the way costs for answering FOI requests are calculated. If approved, they will make the Act virtually useless for all but the most superficial request. The government has blithely admitted it wants to obstruct requestors, particularly journalists and campaigners – precisely the people that in the U.S. quality for a fee waiver because their work in the public interest. In the U.K., these organizations will be grouped and aggregated by type – so any media group will be limited to just two requests a quarter to a particular public body, effectively blocking their ability to do any meaningful specialist investigations. For a corporation like the BBC with tens of thousands of employees this will be the death of FOI usage.

In addition, officials will be able to include in their cost calculations not only the time spent finding and collecting information but also reading, consulting and "thinking" time thus creating an incentive for inefficient bureaucracy.

Leaving aside the ludicrous impracticality of these changes (how will bureaucrats decide the employer of a freelancer?), there is something bizarre about a government putting an axe to its own legislation just two years after it came into force.

So what great disclosures have prompted this U-turn? So far some of the great exposés include restaurant inspections, public officials’ expenses, the amounts spent on consultants, the number of police officers on full-time sick leave, and the number of parolees who have absconded. But centuries of feudal rule have created a civil service and ruling elite deeply opposed to the idea that the "masses" should have any say over what they do, even if it is with public money in the name of public service.

In Scotland, where there’s a tougher FOI law and a tougher enforcement regime, it’s a different story. Leading politician David McLetchie was the first head to roll from FOI when full disclosure of politicians’ expenses revealed "anomalies" in his taxi claims. Perhaps it is to avoid such scrutiny that MPs in our own House of Commons have introduced a bill to exempt themselves entirely from the FOIA. This is currently moving through the House.

The biggest FOI disclosure to date has been publication of E.U. farm subsidies that revealed it wasn’t the small Welsh hill farmer benefiting from tax subsidies but the massive agribusinesses such as Unilever and Nestle, as well as aristocratic landholders such as the Queen, Prince Charles and the Duke of Westminster.

FOI is also useful to counter the massive propaganda machine of government. It is noteworthy that while the government claims the £35 million ($70 million) spent implementing FOI is a waste, it has no trouble justifying £300 million ($600 million) for the Central Office of Communication, a government PR section. The Guardian newspaper used FOI and discovered that despite the Health minister claiming that our National Health Service is "better than ever," more than 13 trusts are bankrupt and many more in dire financial straits. I recently won a case for the minutes of a BBC management meeting where the director was dismissed after a journalist claimed the government had "sexed up" a dossier on Iraq’s nuclear weapons capability. The claim was true, but the minutes reveal a BBC management in blind panic after government attacks.

It isn’t just "quality" papers such as the Guardian and the Times who are using the law. Even tabloids such as the News of the World (nicknamed "News of the Screws" for its sordid investigations) has used FOI most recently to uncover the number of registered sex offenders whom the police have "lost."

But FOI has perhaps been most beneficial to local reporters and local people. British local authorities operate in near Soviet-style secrecy. Decisions are made behind closed doors by mostly one-party Cabinets. Mayors have virtually unchecked power and the public have little access or influence apart from cosmetic public consultations that are rigidly controlled by officials. The sort of open meetings Americans take for granted, where citizens give public testimony, are the stuff of our dreams. Yet we fork over more of our taxes on public services than our American counterparts.

In such a sea of secrecy, FOIA is salvation. Suddenly local people are finding out what poor value they are getting from contracts signed by their elected representatives. The Norwich Evening News used FOI to uncover how local police spent about £70,000 ($140,000) on away days and conferences despite moving into a new £52.3 million ($104 million) headquarters just a few years before. Local reporters have begun digging into local schools to find out the number of pupils expelled for drugs and discipline problems; into local hospitals to find out the amounts paid out in compensation for botched operations; into local councils to find out how much is spent on consultants and travel expenses, and local police and prosecution services to see how many criminals are caught and successfully prosecuted.

Now all this could be in danger. The government will announce in the next month whether it will go ahead with the changes. Why should Americans care what happens in Britain? Two reasons. Our governments have a number of reciprocal information sharing agreements and U.K. reporters often use this to squirrel out information from America that their own government refuses to disclose. If the U.K. were more open, then this tactic could be used by American journalists. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the U.K. still influences many of its former colonies. As such, the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative has protested against the government’s moves to curtail FOIA: “It is imperative that the U.K. implement best practice and set a good example for other Commonwealth member states.”

The United States and U.K. should be standing as beacons for democratic government yet too often it seems our leaders are taking lessons from the worst dictators. We must put our own houses in order and ensure our leaders operate with the same levels of transparency that they demand of others.

Heather Brooke is a freelance journalist and author of "Your Right to Know – A Citizen’s Guide to the Freedom of Information Act," published by Pluto Press. She runs the www.yrtk.org Web site and can be contacted at

- Details

- Written by: Heather Brooke

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?