Health

A new optical device puts the power to detect eye disease in the palm of a hand.

The tool – about the size of a handheld video camera – scans a patient's entire retina in seconds and could aid primary care physicians in the early detection of a host of retinal diseases including diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma and macular degeneration.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) describe their new ophthalmic-screening instrument in a paper published this month in the open-access journal Biomedical Optics Express, published by The Optical Society (OSA).

Although other research groups and companies have created handheld devices using similar technology, the new design is the first to combine cutting-edge technologies such as ultrahigh-speed 3-D imaging, a tiny micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) mirror for scanning, and a technique to correct for unintentional movement by the patient.

These innovations, the authors say, should allow clinicians to collect comprehensive data with just one measurement.

Normally, to diagnose retinal diseases, an ophthalmologist or optometrist must examine the patient in his or her office, typically with table-top instruments. However, few people visit these specialists regularly.

To improve public access to eye care, the MIT group, in collaboration with the University of Erlangen and Praevium/Thorlabs, has developed a portable instrument that can be taken outside a specialist's office.

“Hand-held instruments can enable screening a wider population outside the traditional points of care,” said researcher James Fujimoto of MIT, an author on the Biomedical Optics Express paper. For instance, they can be used at a primary-care physician's office, a pediatrician's office or even in the developing world.

How it works

The instrument uses a technique called optical coherence tomography (OCT), which the MIT group and collaborators helped pioneer in the early 1990s.

The technology sends beams of infrared light into the eye and onto the retina. Echoes of this light return to the instrument, which uses interferometry to measures changes in the time delay and magnitude of the returning light echoes, revealing the cross sectional tissue structure of the retina – similar to radar or ultrasound imaging.

Tabletop OCT imagers have become a standard of care in ophthalmology, and current generation hand-held scanners are used for imaging infants and monitoring retinal surgery.

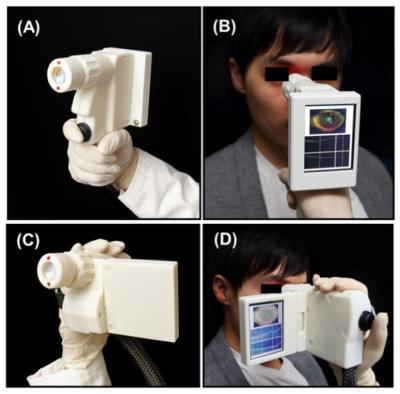

The researchers were able to shrink what has been typically a large instrument into a portable size by using a MEMS mirror to scan the OCT imaging beam.

They tested two designs, one of which is similar to a handheld video camera with a flat-screen display. In their tests, the researchers found that their device can acquire images comparable in quality to conventional table-top OCT instruments used by ophthalmologists.

To deal with the motion instability of a hand-held device, the instrument takes multiple 3-D images at high speeds, scanning a particular volume of the eye many times but with different scanning directions.

By using multiple 3-D images of the same part of the retina, it is possible to correct for distortions due to motion of the operator's hand or the subject's own eye.

The next step, Fujimoto said, is to evaluate the technology in a clinical setting. But the device is still relatively expensive, he added, and before this technology finds its way into doctors' offices or in the field, manufacturers will have to find a way to support or lower its cost.

Why early screening is important

Many people with eye diseases may not even be aware of them until irreversible vision loss occurs, Fujimoto said.

Screening technology is important because many eye diseases should be detected and treated long before any visual symptoms arise.

For example, in a 2003 Canadian study of nearly 25,000 people, almost 15 percent were found to have eye disease – even though they showed no visual symptoms and 66.8 percent of them had a best-corrected eyesight of 20/25 or better.

Problems with undetected eye disease are exacerbated with the rise of obesity and undiagnosed diabetes, Fujimoto said.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 11.3 percent of the U.S. population over the age of 20 has diabetes, even though many do not know it.

In the future, Fujimoto envisions that hand-held OCT technology can be used in many other medical specialties beyond ophthalmology – for example, in applications ranging from surgical guidance to military medicine.

“The hand-held platform allows the diagnosis or screening to be performed in a much wider range of settings,” Fujimoto said. “Developing screening methods that are accessible to the larger population could significantly reduce unnecessary vision loss.”

- Details

- Written by: Editor

Using high-resolution functional MRI (fMRI) imaging in patients with Alzheimer's disease and in mouse models of the disease, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers have clarified three fundamental issues about Alzheimer's: where it starts, why it starts there, and how it spreads.

In addition to advancing understanding of Alzheimer's, the findings could improve early detection of the disease, when drugs may be most effective.

The study was published today in the online edition of the journal Nature Neuroscience.

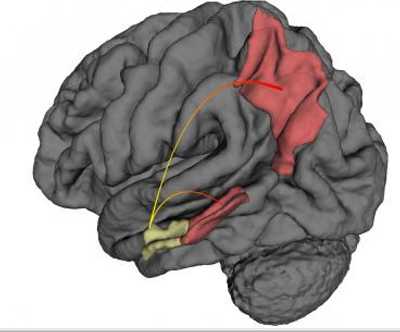

“It has been known for years that Alzheimer's starts in a brain region known as the entorhinal cortex,” said co-senior author Scott A. Small, MD, Boris and Rose Katz Professor of Neurology, professor of radiology, and director of the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center. “But this study is the first to show in living patients that it begins specifically in the lateral entorhinal cortex, or LEC. The LEC is considered to be a gateway to the hippocampus, which plays a key role in the consolidation of long-term memory, among other functions. If the LEC is affected, other aspects of the hippocampus will also be affected.”

The study also shows that, over time, Alzheimer's spreads from the LEC directly to other areas of the cerebral cortex, in particular, the parietal cortex, a brain region involved in various functions, including spatial orientation and navigation.

The researchers suspect that Alzheimer's spreads “functionally,” that is, by compromising the function of neurons in the LEC, which then compromises the integrity of neurons in adjoining areas.

A third major finding of the study is that LEC dysfunction occurs when changes in tau and amyloid precursor protein (APP) co-exist.

“The LEC is especially vulnerable to Alzheimer's because it normally accumulates tau, which sensitizes the LEC to the accumulation of APP. Together, these two proteins damage neurons in the LEC, setting the stage for Alzheimer's,” said co-senior author Karen E. Duff, PhD, professor of pathology and cell biology (in psychiatry and in the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain) at CUMC and at the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

In the study, the researchers used a high-resolution variant of fMRI to map metabolic defects in the brains of 96 adults enrolled in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP). All of the adults were free of dementia at the time of enrollment.

“Dr. Richard Mayeux's WHICAP study enables us to follow a large group of healthy elderly individuals, some of whom have gone on to develop Alzheimer's disease,” said Dr. Small. “This study has given us a unique opportunity to image and characterize patients with Alzheimer's in its earliest, preclinical stage.”

The 96 adults were followed for an average of 3.5 years, at which time 12 individuals were found to have progressed to mild Alzheimer's disease.

An analysis of the baseline fMRI images of those 12 individuals found significant decreases in cerebral blood volume (CBV) – a measure of metabolic activity – in the LEC compared with that of the 84 adults who were free of dementia.

A second part of the study addressed the role of tau and APP in LEC dysfunction. While previous studies have suggested that entorhinal cortex dysfunction is associated with both tau and APP abnormalities, it was not known how these proteins interact to drive this dysfunction, particularly in preclinical Alzheimer's.

To answer this question, explained first author Usman Khan, an MD-PhD student based in Dr. Small's lab, the team created three mouse models, one with elevated levels of tau in the LEC, one with elevated levels of APP, and one with elevated levels of both proteins.

The researchers found that the LEC dysfunction occurred only in the mice with both tau and APP.

The study has implications for both research and treatment. “Now that we've pinpointed where Alzheimer's starts, and shown that those changes are observable using fMRI, we may be able to detect Alzheimer's at its earliest preclinical stage, when the disease might be more treatable and before it spreads to other brain regions,” said Dr. Small. In addition, say the researchers, the new imaging method could be used to assess the efficacy of promising Alzheimer's drugs during the disease's early stages.

The paper is titled, “Molecular drivers and cortical spread of lateral entorhinal cortex dysfunction in preclinical Alzheimer's disease.”

The other contributors are Li Liu, Frank Provenzano, Diego Berman, Caterina Profaci, Richard Sloan and Richard Mayeux, all at CUMC.

- Details

- Written by: Editor

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?