News

- Details

- Written by: Elizabeth Larson

Dogs available for adoption this week include mixes of Alaskan husky, American blue heeler, Anatolian shepherd, border collie, German shepherd, Great Pyrenees, Labrador Retriever, pit bull terrier, Rottweiler and Weimaraner.

Dogs that are adopted from Lake County Animal Care and Control are either neutered or spayed, microchipped and, if old enough, given a rabies shot and county license before being released to their new owner. License fees do not apply to residents of the cities of Lakeport or Clearlake.

Those dogs and the others shown on this page at the Lake County Animal Care and Control shelter have been cleared for adoption.

Call Lake County Animal Care and Control at 707-263-0278 or visit the shelter online for information on visiting or adopting.

The shelter is located at 4949 Helbush in Lakeport.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

- Details

- Written by: Robert Sanders

Most birds that flit through dense, leafy forests have a strategy for maneuvering through tight windows in the vegetation — they bend their wings at the wrist or elbow and barrel through.

But hummingbirds can't bend their wing bones during flight, so how do they transit the gaps between leaves and tangled branches?

A study published today in the Journal of Experimental Biology shows that hummingbirds have evolved their own unique strategies — two of them, in fact. These strategies have not been reported before, likely because hummers maneuver too quickly for the human eye to see.

For slit-like gaps too narrow to accommodate their wingspan, they scooch sideways through the slit, flapping their wings continually so as not to lose height.

For smaller holes — or if the birds are already familiar with what awaits them on the other side — they tuck their wings and coast through, resuming flapping once clear.

“For us, going into the experiments, the tuck and glide would have been the default. How else could they get through?” said Robert Dudley, a professor of integrative biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and senior author of the paper. “This concept of sideways motion with a total mix-up of the wing kinematics is quite amazing — it's a novel and unexpected method of aperture transit. They're changing the amplitude of the wing beats so that they're not dropping vertically when they do the sideways scooch.”

Using the slower sideways scooch technique may allow birds to better assess upcoming obstacles and voids, thereby reducing the likelihood of collisions.

“Learning more about how animals negotiate obstacles and other 'building-blocks' of the environment, such as wind gusts or turbulent regions, can improve our overall understanding of animal locomotion in complex environments,” noted first author Marc Badger, who obtained his Ph.D from UC Berkeley in 2016. “We still don't know very much about how flight through clutter might be limited by geometric, aerodynamic, sensory, metabolic or structural processes. Even behavioral limitations could arise from longer-term effects, such as wear and tear on the body, as hinted at by the shift in aperture negotiation technique we observed in our study.”

Understanding the strategies that birds use to maneuver through a cluttered environment may eventually help engineers design drones that better navigate complex environments, he noted.

“Current remote control quadrotors can outperform most birds in open space across most metrics of performance. So is there any reason to continue learning from nature?” said Badger. “Yes. I think it's in how animals interact with complex environments. If we put a bird's brain inside a quadrotor, would the cyborg bird or a normal bird be better at flying through a dense forest in the wind? There may be many sensory and physical advantages to flapping wings in turbulent or cluttered environments.”

Obstacle course

To discover how hummingbirds — in this case, four local Anna’s hummingbirds (Calypte anna) — slip through tiny openings, despite being unable to fold their wings, Badger and Dudley teamed up with UC Berkeley students Kathryn McClain, Ashley Smiley and Jessica Ye.

“We set up a two-sided flight arena and wondered how to train birds to fly through a 16-square- centimeter gap in the partition separating the two sides,” Badger said, noting that the hummingbirds have a wingspan of about 12 centimeters (4 3/4 inches). “Then, Kathryn had the amazing idea to use alternating rewards.”

That is, the team placed flower-shaped feeders containing a sip of sugar solution on both sides of the partition, but only remotely refilled the feeders after the bird had visited the opposite feeder. This encouraged the birds to continually flit between the two feeders through the aperture.

The researchers then varied the shape of the aperture, from oval to circular, ranging in height, width and diameter, from 12 cm to 6 cm, and filmed the birds’ maneuvers with high-speed cameras. Badger wrote a computer program to track the position of each bird’s bill and wing tips as it approached and passed through the aperture.

They discovered that as the birds approached the aperture, they often hovered briefly to assess it before traveling through sideways, reaching forward with one wing while sweeping the second wing back, fluttering their wings to support their weight as they passed through the aperture. They then swiveled their wings forward to continue on their way.

“The thing is, they have to still maintain weight support, which is derived from both wings, and then control the horizontal thrust, which is pushing it forward. And they're doing this with the right and left wing doing very peculiar things,” Dudley said. “Once again, this is just one more example of how, when pushed in some experimental situation, we can elicit control features that we don't see in just a standard hovering hummingbird.”

Alternatively, the birds swept their wings back and pinned them to their bodies, shooting through — beak first, like a bullet — before sweeping the wings forward and resuming flapping once safely through.

“They seem to do the faster method, the ballistic buzz-through, when they get more acquainted with the system,” Dudley said.

Only when approaching the smallest apertures, which were half a wingspan wide, would the birds automatically resort to the tuck and glide, even though they were unfamiliar with the setup.

The team pointed out that only about 8% of the birds clipped their wings as they passed through the partition, although one experienced a major collision. Even then, the bird recovered quickly before successfully reattempting the maneuver and going on its way.

“The ability to pick among several obstacle negotiation strategies can allow animals to reliably squeeze through tight gaps and recover from mistakes,” Badger noted.

Dudley hopes to conduct further experiments, perhaps with a sequence of different apertures, to determine how birds navigate multiple obstacles.

The work was funded primarily by a CiBER-IGERT grant from the National Science Foundation (DGE-0903711).

Robert Sanders writes for the UC Berkeley News Center.

- Details

- Written by: Huw Morgan, Aberystwyth University

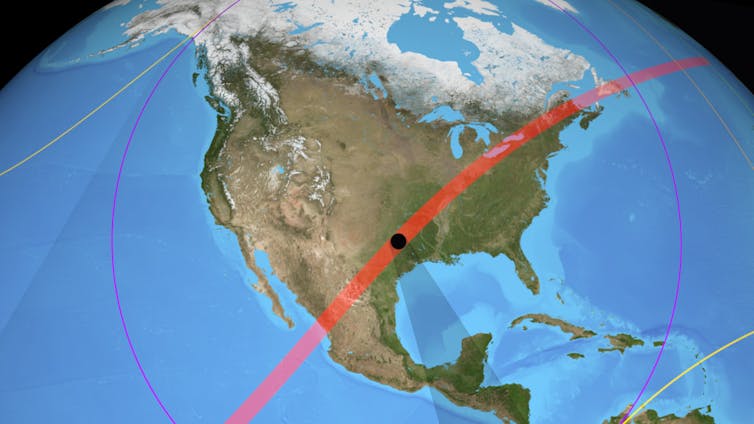

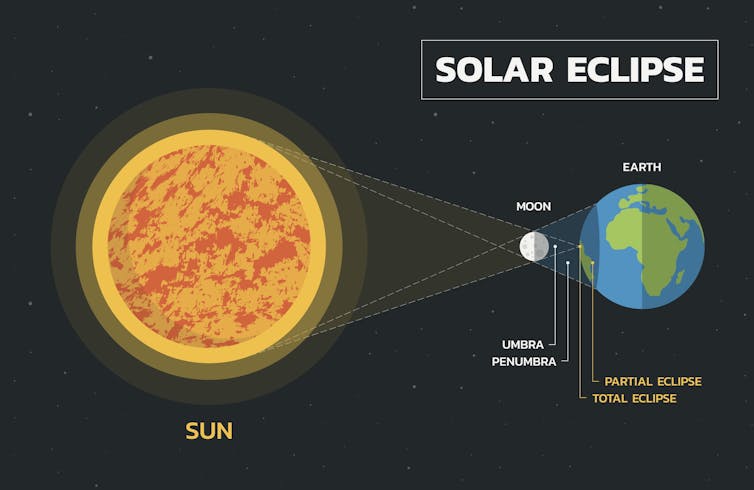

A total solar eclipse takes place on April 8 across North America. These events occur when the Moon passes between the Sun and Earth, completely blocking the Sun’s face. This plunges observers into a darkness similar to dawn or dusk.

During the upcoming eclipse, the path of totality, where observers experience the darkest part of the Moon’s shadow (the umbra), crosses Mexico, arcing north-east through Texas, the Midwest and briefly entering Canada before ending in Maine.

Total solar eclipses occur roughly every 18 months at some location on Earth. The last total solar eclipse that crossed the US took place on August 21 2017.

An international team of scientists, led by Aberystwyth University, will be conducting experiments from near Dallas, at a location in the path of totality. The team consists of PhD students and researchers from Aberystwyth University, Nasa Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, and Caltech (California Institute of Technology) in Pasadena.

There is valuable science to be done during eclipses that is comparable to or better than what we can achieve via space-based missions. Our experiments may also shed light on a longstanding puzzle about the outermost part of the Sun’s atmosphere – its corona.

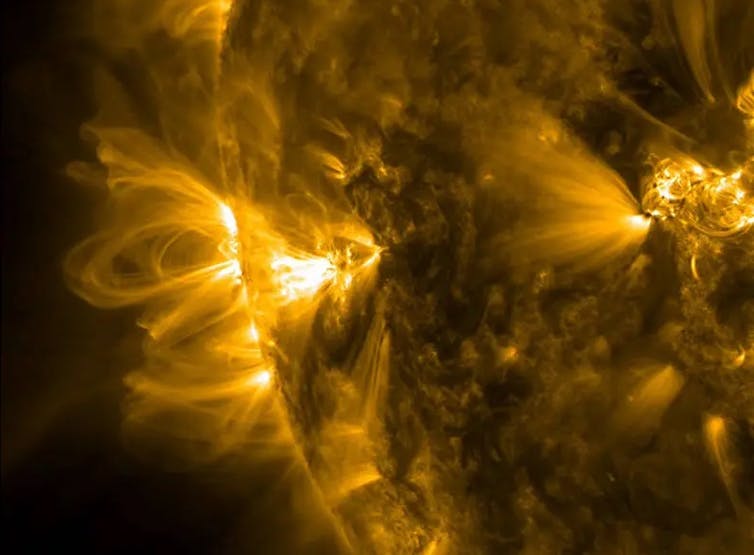

The Sun’s intense light is blocked by the Moon during a total solar eclipse. This means that we can observe the Sun’s faint corona with incredible clarity, from distances very close to the Sun, out to several solar radii. One radius is the distance equivalent to half the Sun’s diameter, about 696,000km (432,000 miles).

Measuring the corona is extremely difficult without an eclipse. It requires a special telescope called a coronagraph that is designed to block out direct light from the Sun. This allows fainter light from the corona to be resolved. The clarity of eclipse measurements surpasses even coronagraphs based in space.

We can also observe the corona on a relatively small budget, compared to, for example, spacecraft missions. A persistent puzzle about the corona is the observation that it is much hotter than the photosphere (the visible surface of the Sun). As we move away from a hot object, the surrounding temperature should decrease, not increase. How the corona is heated to such high temperatures is one question we will investigate.

We have two main scientific instruments. The first of these is Cip (coronal imaging polarimeter). Cip is also the Welsh word for “glance”, or “quick look”. The instrument takes images of the Sun’s corona with a polariser.

The light we want to measure from the corona is highly polarised, which means it is made up of waves that vibrate in a single geometric plane. A polariser is a filter that lets light with a particular polarisation pass through it, while blocking light with other polarisations.

The Cip images will allow us to measure fundamental properties of the corona, such as its density. It will also shed light on phenomena such as the solar wind. This is a stream of sub-atomic particles in the form of plasma – superheated matter – flowing continuously outward from the Sun. Cip could help us identify sources in the Sun’s atmosphere for certain solar wind streams.

Direct measurements of the magnetic field in the Sun’s atmosphere are difficult. But the eclipse data should allow us to study its fine-scale structure and trace the field’s direction. We’ll be able to see how far magnetic structures called large “closed” magnetic loops extend from the Sun. This in turn will give us information about large-scale magnetic conditions in the corona.

The second instrument is Chils (coronal high-resolution line spectrometer). It collects high-resolution spectra, where light is separated into its component colours. Here, we are looking for a particular spectral signature of iron emitted from the corona.

It comprises three spectral lines, where light is emitted or absorbed in a narrow frequency range. These are each generated at a different range of temperatures (in the millions of degrees), so their relative brightness tells us about the coronal temperature in different regions.

Mapping the corona’s temperature informs advanced, computer-based models of its behaviour. These models must include mechanisms for how the coronal plasma is heated to such high temperatures. Such mechanisms might include the conversion of magnetic waves to thermal plasma energy, for example. If we show that some regions are hotter than others, this can be replicated in models.

This year’s eclipse also occurs during a time of heightened solar activity, so we could observe a coronal mass ejection (CME). These are huge clouds of magnetised plasma that are ejected from the Sun’s atmosphere into space. They can affect infrastructure near Earth, causing problems for vital satellites.

Many aspects of CMEs are poorly understood, including their early evolution near the Sun. Spectral information on CMEs will allow us to gain information on their thermodynamics, and their velocity and expansion near the Sun.

Our eclipse instruments have recently been proposed for a space mission called Moon-enabled solar occultation mission (Mesom). The plan is to orbit the Moon to gain more frequent and extended eclipse observations. It is being planned as a UK Space Agency mission involving several countries, but led by University College London, the University of Surrey and Aberystwyth University.

We will also have an advanced commercial 360-degree camera to collect video of the April 8 eclipse and the observing site. The video is valuable for public outreach events, where we highlight the work we do, and helps to generate public interest in our local star, the Sun.![]()

Huw Morgan, Reader in Physical Sciences, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

- Details

- Written by: Lake County News reports

LAKE COUNTY, Calif. — Congressman Mike Thompson visited Lake County on Tuesday, spending time with local businesses and meeting with tribal leaders.

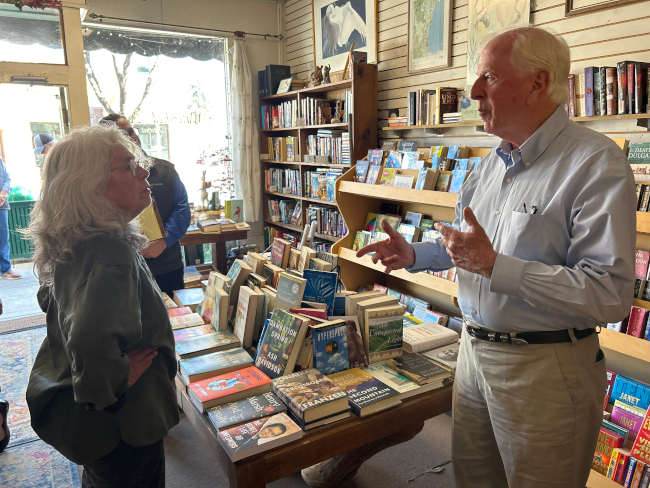

Thompson joined the Lakeport Economic Development Advisory Committee, or LEDAC, to tour Lakeport’s small businesses.

They discussed how they can work together to strengthen the local economy and help create jobs.

Among the businesses Thompson visited were On the Waterfront, Watershed Bookstore, Marcel’s French Bakery and Cafe, Veronica’s Jewelers and Wine in the Willows.

Also on Tuesday, Thompson met with Robinson Rancheria Band of Pomo Indians Tribal Chairman Beniakem Cromwell and tribal leadership to discuss how they can work together to preserve and protect Clear Lake hitch.

They also discussed how to support the tribe’s efforts to protect the community against fires and other natural disasters.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?