Opinion

March 16-22 is Sunshine Week, the time to discuss and explore the concept of open government. The following column, provided by Sunshineweek.org, in one of a series Lake County News will offer this week as part of the important discussion of keeping government information available to the public.

In 2005, then-Deputy Attorney General James Comey told colleagues at the Justice Department that they would be "ashamed" when a legal memorandum on forceful interrogation of prisoners eventually became public. In fact, however, disclosure of such secret Bush administration documents may be the only way to begin to overcome the palpable shame that is already felt by many Americans at the thought that their government has engaged in abusive interrogations, secret renditions or unchecked surveillance.

The next president will have the authority to declassify and disclose any and all records that reflect the activities of executive branch agencies. Although internal White House records that document the activities of the outgoing president and his personal advisers will be exempt from disclosure for a dozen years or so, every Bush administration decision that was actually translated into policy will have left a documentary trail in one or more of the agencies, and all such records could be disclosed at the discretion of the next president.

A new president may find it advantageous to quickly distinguish himself (or herself) from the current administration and its policies. By exposing what is "shameful" in our recent past the new administration could demonstrate a clean break with its predecessor, and lay the foundation for a more transparent and accountable presidency.

Most of the leading candidates from both parties have specifically criticized the secrecy of the Bush administration. In particular, those who are now serving in Congress have repeatedly been on the receiving end of White House secrecy, and may be all the more motivated to repudiate it in deed as well as in word.

"Excessive administration secrecy... feeds conspiracy theories and reduces the public's confidence in government," Sen. John McCain (R-Ariiz.) has said. "I'll turn the page on a growing empire of classified information," said Sen. Barack Obama (D-Ill.). "We'll protect sources and methods, but we won't use sources and methods as pretexts to hide the truth." "We need a return to transparency and a system of checks and balances, to a president who respects Congress's role of oversight and accountability," said Sen. Hillary Clinton (D-N.Y.).

The most troubling and the most secretive Bush administration actions are those in the realm of national security policy, and that is the first place, though not the last, where the next administration could constructively shed new light. It goes without saying that genuine national security secrets such as confidential sources and legally authorized intelligence methods should be protected from disclosure. But that still leaves ample room for revelation of fundamental policy choices, and certainly of any illegal or embarrassing ("shameful") actions that may have been improperly classified to evade accountability. For example:

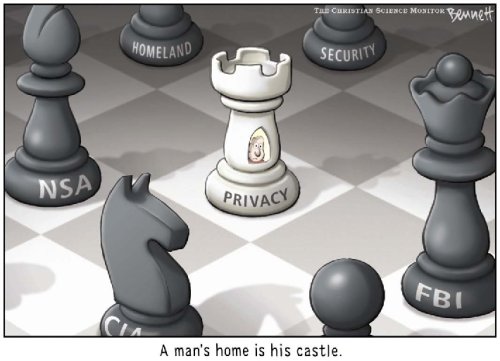

1. Domestic Surveillance. The White House is seeking and Congress is poised to grant retroactive immunity for telephone companies that assisted the administration in its surveillance activities. But immunity for what? "This administration may have enjoyed completely unrestrained access to the communications of virtually every American," said Sen. James Webb (D-Va.) earlier this month. "Do we know this to be the case? I cannot be sure. One reason I cannot be sure is that I have been denied access to review the documents that may answer these questions about the process." Such uncertainty should be remedied once and for all by official disclosure.

2. Interrogation and Torture. After months and years of awkward circumlocution, CIA Director Michael V. Hayden admitted on Feb. 5 that U.S. interrogators had subjected three al Qaeda prisoners to waterboarding, or simulated drowning. But the acknowledgment raised more questions than it answered. On what authority did interrogators engage in what has long been considered a prosecutable action? What other coercive interrogation techniques have been adopted? If waterboarding is now deemed permissible under some circumstances, is there any interrogation technique that the administration would still rule out? What has been the humanitarian cost around the world? As a practical matter, has the U.S. government effectively legitimized torture? If there is to be accountability for the interrogation of prisoners in U.S. custody, the first step must be a forthright disclosure of what the Bush administration has done.

3. Extraordinary Rendition. The U.S. government has seized suspected terrorists and transported them without any semblance of judicial process to foreign countries where they have been tortured, a process known as "extraordinary rendition." In one particularly outlandish case, a Canadian national named Maher Arar was arrested in New York on the basis of erroneous information and deported by the U.S. government to Syria, where he was brutally interrogated over the course of a year. Following his release, the government of Canada concluded that his detention was a mistake and issued a formal apology. But the Bush administration declined to follow suit.

4. And Much More. The topics noted above became controversial due to press reports, leaks, whistleblower accounts, lawsuits and similar indications. But there is reason to wonder what other yet unknown deviations from accepted practice the Bush administration might have pursued under cover of secrecy. Of the 54 National Security Presidential Directives issued by the Bush administration to date, the titles of only about half have been publicly identified. There is descriptive material or actual text in the public domain for only about a third. In other words, there are dozens of undisclosed presidential directives that define U.S. national security policy and task government agencies, but whose substance is unknown either to the public or, as a rule, to Congress. Given what we do know of the character of the present administration, this whole mechanism of executive authority seems in need of public ventilation.

And so here are some questions that journalists could usefully pose to the presidential candidates:

Q: Will you disclose the full scope of Bush administration domestic surveillance activities affecting American citizens, including all surveillance actions that were undertaken outside of the framework of law, as well as the legal opinions that were generated to justify them?

Q: Will you specify precisely what sort of coercive interrogation techniques were employed by the Bush administration, as well as their purported justifications, so that the nation may openly decide whether to embrace or to repudiate such techniques?

Q: Will you renounce the practice of extraordinary rendition that is not sanctioned by any judicial process? Will you issue a formal apology to Maher Arar for his mistaken arrest, deportation and torture?

Q: Will you disclose at least a summary account of the contents of each of the Bush administration's National Security Presidential Directives, as well as your own?

Aftergood directs the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists and writes the Secrecy News blog. The column above originally appeared in the Feb. 7 edition of the Nieman Watchdog.

{mos_sb_discuss:4}

- Details

- Written by: Steven Aftergood

March 16-22 is Sunshine Week, the time to discuss and explore the concept of open government. The following column, provided by Sunshineweek.org, in one of a series Lake County News will offer this week as part of the important discussion of keeping government information available to the public.

It's been a few tough years for open government in the United States. Security fears, combined with a president determined to protect his prerogatives, have kept advocates of transparency playing defense. There are signs that the tables are beginning to turn, but it's been a draining fight to maintain laws and policies built up over decades.

However, there's better news elsewhere. Since 2001, almost 30 other countries have adopted U.S.-style Freedom of Information laws, which provide citizens with a right to government documents. Among the most recent adopters are the two most populous countries on earth: India and China. The right to information, once known only to the millions living in wealthy democracies, is being extended to billions of the world's poor.

India might be the most fascinating laboratory for freedom of information in the world today. The country's center-left government adopted a national Right to Information Act soon after its election in 2004. The law is sweeping in scope: it covers not just federal agencies, but also 35 states and territories, and thousands of lower-level governments.

The media quickly began exploring the potential of the new law. Last month, the national newsmagazine India Today featured an exposé on the travel habits of the country's unusually large Cabinet that relied on documents gleaned through 60 formal requests under the new law. In total, the magazine found, 71 Cabinet ministers had logged over 10 million miles of international travel in under four years. It takes "Olympian stamina" to use the law, says editor Aroon Purie, but the results have helped to hold ministers accountable for abuse of taxpayer money.

More remarkable is the way in which disadvantaged Indians have seized on the new law to remedy grievances against local officials. In Chandrapura — a poor rural village of 2,500 in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh — citizens used the Right to Information Act to pry out information about long-promised development projects. Officials eventually relented, providing the village with access to electricity and a bridge that gives access to markets during the long rainy season.

Journalists Maneesh Pandey and Misha Singh say that Chandrapura is a "shining example" of how access to information is changing life for the poor. In Keolari, another village in Madhya Pradesh, the law was recently used to prove that a local councilor had unlawfully taken control of a well that is one of the village's only sources of water. In the Indian capital, Delhi, local groups rely on the law to expose payments to contractors for public works that were never completed. A civic organizer in Mumbai says the Right to Information Act "is like a brahmastra," a devastating weapon created by Brahma, the Hindu god of creation.

In truth, however, it's not just the law that makes a difference. It's the combination of law, a free press, and civic groups that persist despite threats and assaults. Last December, an activist in the state of Rajasthan was beaten outside a government office after making a request for documents about a local employment program. Earlier, an organizer in Delhi had her throat slit while working to extract details about food rations for the poor.

China is another intriguing testing-ground for the right to information. Major cities such as Guangzhou and Shanghai have had disclosure rules for several years. Officials in Shanghai received more than 30,000 requests from citizens in the 18 months after the adoption of their 2004 policy. One district in Shanghai actually organized a team of 300 volunteers to help citizens root information out of local offices.

Last spring, China's central government went a step further, adopting a national Freedom of Information regulation. The regulation, which goes into effect in just six weeks, will cover all levels of government, as India's law does.

A natural question is why the leaders of a one-party state would be eager to adopt a policy that is usually sold as a tool for limiting governmental power. But China's leaders have their own troubles, for which transparency seems the right prescription. The legitimacy of the entire regime is threatened by bureaucratic corruption and incompetence. The rising number of "mass group incidents" — that is, protests and riots — is one sign of growing anger over the government's inability to deal with rapid growth, urbanization, and environmental decay.

China's leaders hope that a Freedom of Information policy will provide an outlet for citizen frustration and impose discipline on lower tiers of the Chinese state. It's a paradox: a "top-down policy," as one analyst says, aimed at enlisting ordinary people to serve as watchdogs on behalf of the center.

It remains to be seen how well this policy will work. The policy applies across the largest bureaucratic complex on the planet, and there are bound to be immense challenges in assuring that lower-level officials pay attention to directions from distant Beijing. The lack of a free press, limited political rights, and a weak judiciary also complicate matters. What good is information, after all, if you lack the capacity to act on it?

Still, it is an extraordinary experiment. If Chinese and Indian policies succeed, it will be an accomplishment that dwarfs any of the transient setbacks in the United States and other western countries. Over 2 billion people — more than one third of the world's population — will see the promise of more open government.

Roberts is a professor of public administration in the Maxwell School of Syracuse University. His book, "Blacked Out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age," is published by Cambridge University Press. His Web address is http://www.aroberts.us.

{mos_sb_discuss:4}

- Details

- Written by: Alasdair Roberts

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?