While on the road, you’re probably thinking more about your destination than the pavement you’re driving over. But building roads requires a host of engineering feats, from developing the right pavement materials to using heavy equipment to lay them down. The better they’re built, the longer roads last and the fewer construction delays drivers have to endure.

I am an engineer who does research on materials used in roads. Scholars in my field are working to develop materials that can make roads stronger and last longer.

Road materials

So, what are roads really made of? The simple answer is that they are made of typical construction materials such as aggregates – soils and rocks – as well as asphalt binder and Portland cement, which act like glue to bond it all together.

Asphalt binder is refined from crude oil. From crude oil, refiners first extract gasoline, kerosene and oil, and what remains at the bottom becomes the asphalt. Portland cement is manufactured using several different ingredients, including limestone, sand, clay, silica and alumina.

Engineers compact the mixture of asphalt binder and aggregates together at an elevated temperature, about 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius), which glues the aggregates together into the final product, called asphalt concrete.

If they’re using Portland cement rather than asphalt binder to glue the aggregates together, the engineers cure the mixture of the cement and aggregates with water through a process called hydration.

Hydration bonds the cement to the aggregates to make the product, called Portland cement concrete, stronger. With this process, there’s no external heating involved.

Pavement structure

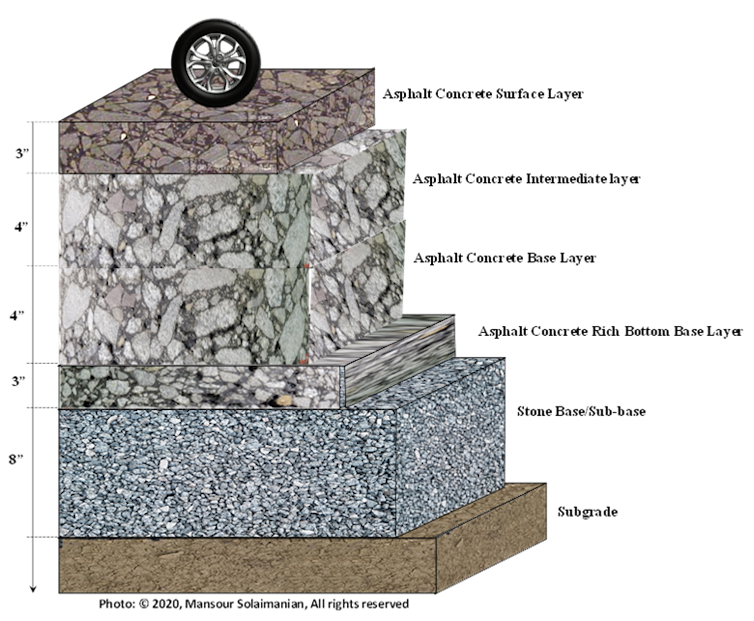

Asphalt concrete’s pavement structure typically has three main layers: the base layer, the intermediate layer and the surface layer.

Engineers call the existing ground where the pavement goes the subgrade. On top of the subgrade goes a new layer of unbound soil and stone, where the aggregates aren’t glued together. This is called the subbase, or unbound aggregate base.

The base layer can be either stones packed together without any binding agent or a combination of stone and asphalt binder.

Once road builders make the base, it is time to build the asphalt concrete layers: the base layer, the intermediate layer and the surface layer. All these layers contain the aggregates – the pieces of rock and sand – glued together with the asphalt binder in some way.

Engineers determine how many layers to build and how thick to make each layer by figuring out how much traffic will drive over the road. The more traffic, the thicker the pavement needs to be. For example, on interstate highways, the depth of the layers combined could be 20 inches (51 centimeters) or more.

Building a strong road

The road builders place the material on the road with an asphalt paving machine called a paver. An operator runs the paver, which takes the materials from a truck and places them on the road. After that, heavy-duty rollers compact it down, make it strong and get it ready for vehicles.

For a strong and durable road, engineers first pick the best subgrade, or place on top of which to build pavement. If the subgrade is too weak, the road might crack and fail – even if the pavement uses the best materials.

First, the road builders use rollers to pack the subgrade down. Once they’ve compacted the subgrade, they place the stone aggregates directly on top of the subgrade and compact them down. This aggregate base on the subgrade provides a sturdy foundation for the asphalt layers.

If the road builders do not use the right materials, or do not put them together correctly, or do not design the pavement structure for the expected traffic, then the road can crack, rut and fail.

Cracking occurs either at extremely low temperatures or from heavy trucks and buses repeatedly driving over the road. Rutting, which refers to noticeable impressions in the road’s surface, occurs mostly during summer heat under heavy trucks or at road intersections.

Potholes are a big road problem you’ve probably seen before. They often show up in the spring after water trapped in the pavement freezes over winter and then melts in spring. This melting process weakens the road, making it more breakable. Then, when vehicles drive over it, they can create potholes.

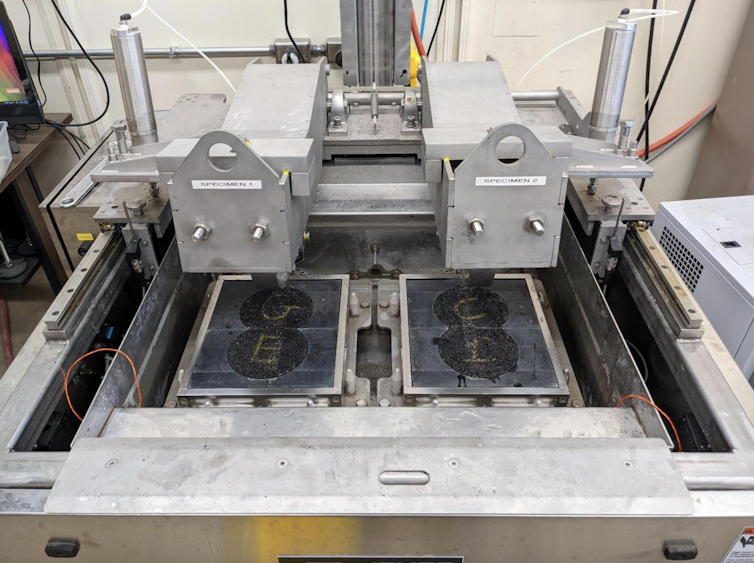

Before the road gets built, the materials undergo testing in a laboratory to make sure they can stand the loads from traffic and environment.

Engineers in the lab expose the pavement materials to both freezing and very hot temperatures to make sure they can withstand any weather. They also expose the pavement materials to water to make sure the materials will not fall apart if it rains or floods.

At the Penn State pavement laboratory, my team is testing asphalt mixtures to which we’ve added substances called modifiers. These include special polymers and fibers that could make the road stronger.

The next time you’re on the road, remember that it takes a good amount of engineering and tremendous teamwork to create that smooth pavement surface you drive on.![]()

Mansour Solaimanian, Research Professor, Larson Pennsylvania Transportation Institute, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?